By MARLENE L. DAUT

On February 6, 1928, the New York Times published an article written from the city of Port-au-Prince by the famous aviator Colonel Charles Lindbergh. Titled “Lindbergh Studies Ruins in Haiti While on His Flight to Its Capital,” Lindbergh, most famous for having flown the first non-stop transatlantic flight in 1927, described how taking a northwest route from Santo Domingo, he flew over the city of Santiago in the Dominican Republic before heading in the direction of the northern city of Cap-Haïtien. As he circled low over Haiti's former capital, which King Henry Christophe once renamed Cap-Henry after himself, Lindbergh noticed a structure that he had only previously heard of but had never seen with his own eyes: the Citadelle Laferrière, known as the Citadelle Henry under Christophe’s reign.

“I had been told of this citadel [sic],” Lindbergh wrote, “which is considered by men who have seen it to be an eighth wonder of the world, and I made a special point of visiting it.” “It is well worth a much longer visit than I was able to give it,” he added. Lindbergh did not land his plane in northern Haiti that day. Yet even from the sky he could observe that the “enormous fortress” had “thick, solid-looking walls, which must be in places 200 feet high.”

Lindbergh grew so intrigued that he sought to get closer. “I flew down within a few feet of the citadel in order to inspect it,” he continued. “The only things I know to compare it to in magnitude are the ancient pyramids in Mexico. Both of these ruins are the most impressive I have seen.”

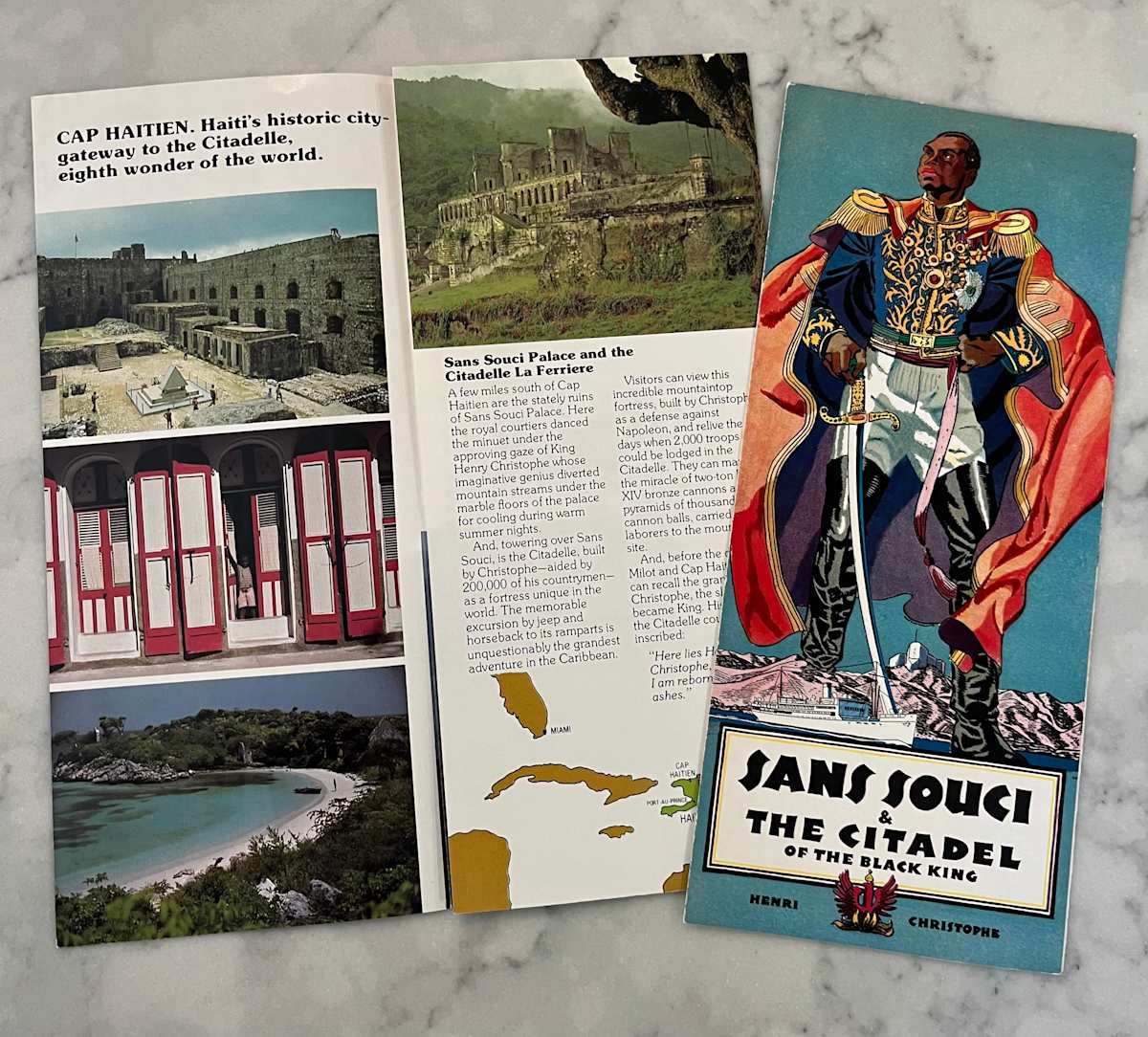

Lindbergh was hardly alone in his veneration for the Citadelle, completed under Christophe’s rule in 1813, and which stands as the largest fortress in North America and a UNESCO World Heritage Site. In a 1930 article, F.E. Evans, a U.S. military colonel stationed in Haiti during the U.S. Occupation, wrote: “There is no more impressive or spectacular ruin in the New World than the famous Citadel, 14 miles south of Cap Haïtien, often called ‘the eighth wonder of the world’.” Indeed, the Citadelle has long been admired by Haiti’s friends and foes.

For his part, the Harlem Renaissance-era writer Mercer Cook—most well known for having translated with Langston Hughes the Haitian author Jacques Roumain’s Masters of the Dew (1947) (Gouverneurs de la rosée [1944])—called King Henry’s fortress “the most regal structure ever raised in the New World.”

(Ca. 1970s vintage pamphlets: “Haiti: Cap Haïtien…and the Mighty Citadelle" and "Sans Souci & The Citadel of the Black King")

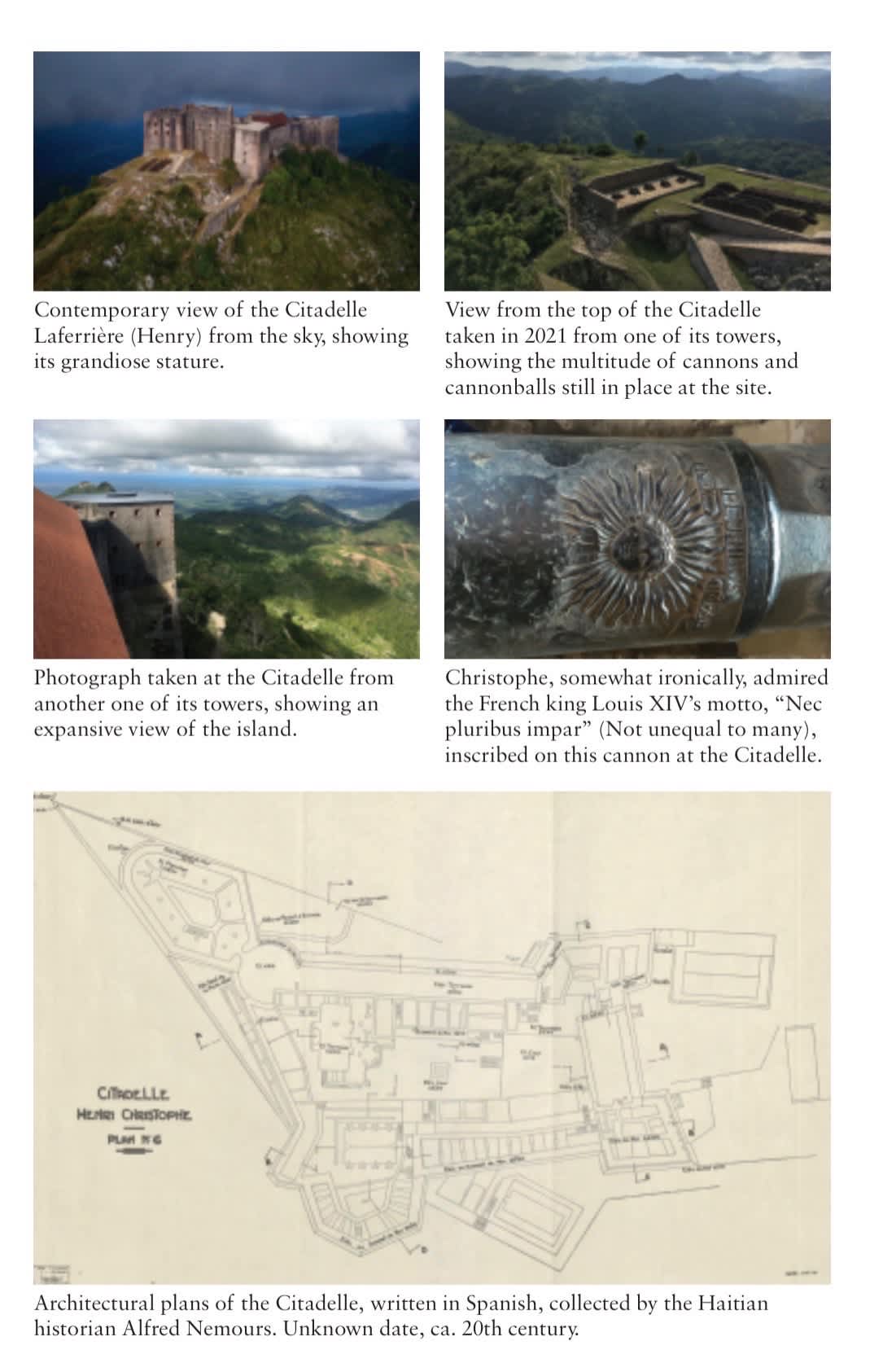

It is hard to fully capture the magnificence of the awe-inspiring Citadelle, with its four angled towers, which the Comte de Limonade, a member of Christophe’s aristocracy, described as “connected to each other, by levels of walls resembling curtains, to form an irregular quadrilateral edifice that encloses a vast place d’armes.” Covering about one hectare, or about two and a half acres, the unrivaled design for “that majestic boulevard of independence,” in the words of Limonade, “was built on the ridged summit of one of the highest mountains on the island, from which one discovers, on its left side, the island of La Tortue, and the mirror of its superb channel; opposite, the hills and the town of Cap-Henry, its port, and the vast expanse of the seas; on the right, La Grange, Monte Cristi, the city of Fort Royal [Fort-Liberté], the bay of Mancenille, and the surrounding mountains.”

With batteries named for Queen Marie-Louise, the princesses (Améthyste and Athénaïre), and the royal prince (Victor-Henry), and fortified with “exceptionally thick walls,” the structure was all at once a prison, a storehouse for weapons, and a military guard post. It reportedly housed more than fifty thousand guns, in addition to sabers, machetes, firearms of all kinds, darts meant to be thrown from the parapets at enemies, millions of bullets, along with thousands of tons of powder and saltpeter, all stored in its humongous depots. There were also cellars stocked with enough food to provide provisions for months. The food stores complemented the shelters that could house ten thousand individuals in case of French re-invasion. Vast as a veritable city, the Citadelle housed its own army corps, pharmacy, printing press, and hospital too. Containing its own separate palace as well, the Citadelle was equipped for King Henry to govern safely from its heights, with his family in tow, if necessary.

(Images from The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe)

Yet not everyone who has visited, or at the very least written about, the Citadelle has held equal reverence for the tortured history of constant threats to Haitian sovereignty that encouraged King Henry to bring the fortress into being. In the St. Lucian writer Derek Walcott’s play, Henri Christophe(1949), written when the playwright was just 19-years old, the priest who crowned Christophe cynically declares, “God, what a waste of blood, these cathedrals, castles, built; Bones in the masonry, skulls in the architrave, Tired masons falling from the chilly turrets.” In his famous book of essays, What the Twilight Says (1957), Walcott expressed even more clearly why he found it difficult to admire all that the Haitian king had tried to build. Walcott remarked that while King Henry’s enormous fortress marked “the slave’s emergence from bondage,” at the same time it suggested “the slave had surrendered one Egyptian darkness for another.”

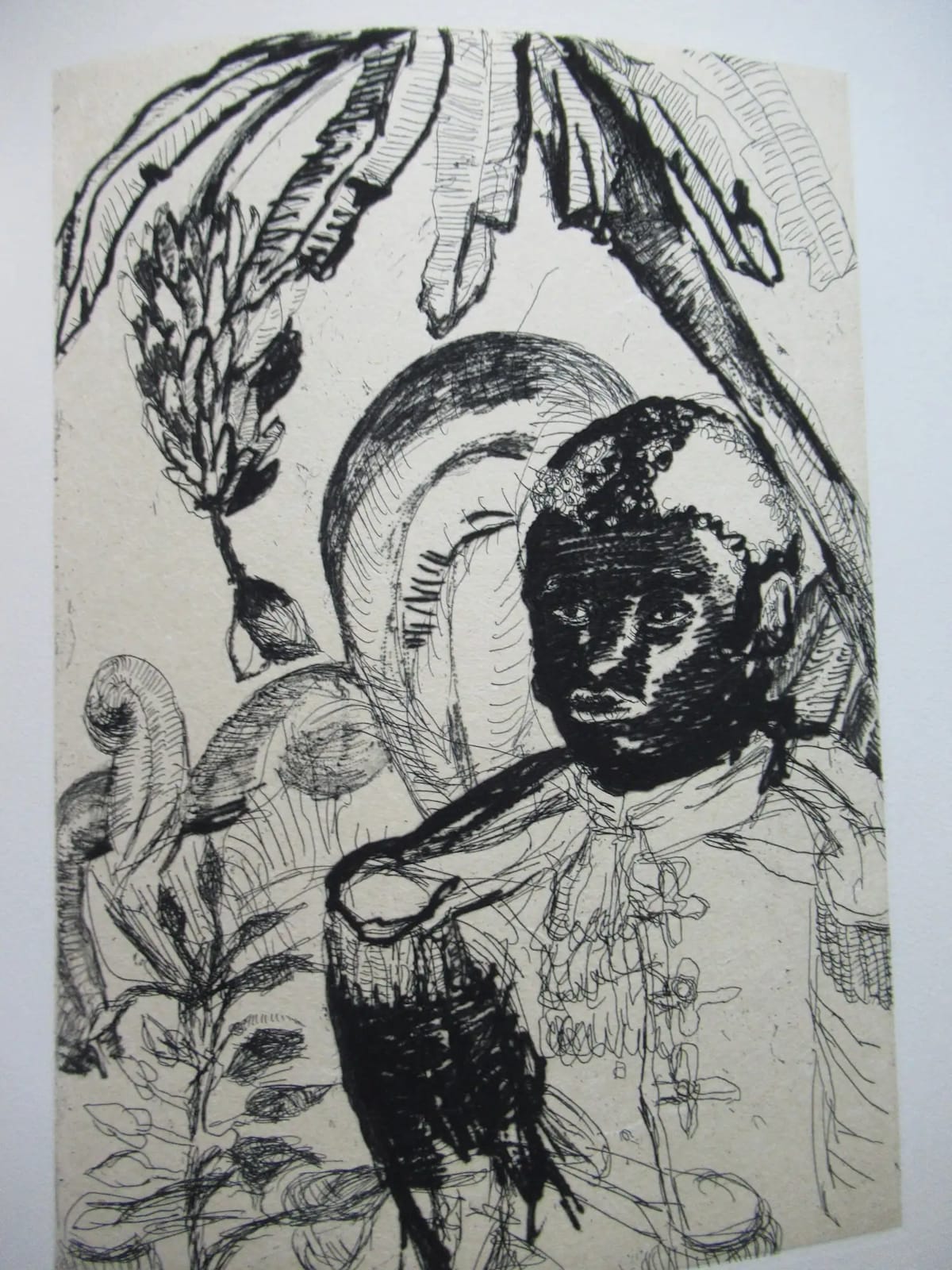

The famous Swiss-born Cuban author Alejo Carpentier, in his novel The Kingdom of this World (originally published in Spanish in 1957), also viewed the Citadelle with the eyes of a skeptic. The king of Haiti was “a monarch of incredible exploits,” Carpentier wrote, before adding that Christophe cut the throats of bulls everyday “so that their blood could be added to the mortar to make [his] fortress impregnable.”

(Etching of Christophe by John Hersey and Roberto Juarez from a 1987 English edition of The Kingdom of this World)

While both Walcott and Carpentier had been clearly influenced by 19th-century British and U.S. writers who had painted Haiti’s king as an uncommon tyrant in the decades following his death in 1820, Lindbergh also seems to have also been acquainted with the various circulating mythologies of Christophe. First acknowledging, “I understand it was built by Christopher [sic] as a last refuge for the Haitians,” in case the “French might return and attempt to recover their lost colony and reestablish slavery,” Lindbergh added, “according to the legend, it was on one of the battlements of this citadel that Christopher marched an entire company over one of the precipitous walls in order to demonstrate the discipline of his troops.” Lindbergh concluded, nevertheless, “Considering the difficulty of the construction, and the immense scale on which it is built, this citadel is an astonishing work.”

Christophe was a complex and vexing leader to be sure. But allowing for and accepting the experience of awe when visiting the truly breathtaking Citadelle does not require co-signing Christophe’s reign or even agreeing with his particular vision of Haitian sovereignty.

Historically, guides in Haiti who take visitors up to the Citadelle and through the ruins of Christophe’s equally imposing Palace at San-Souci have had no trouble explaining the triumphs and the failures, the paradoxes and the promises of Haiti’s first, last, and only king. “King Christophe, our great black leader was too ambitious for the people of Haiti,” said guide Louis Mercier to a group of tourists, as reported in a New York Times profile in March 1941. “He built schools, castles, palaces, roads, churches, hospitals, but in the end the people were driven to work too hard, and they turned on him.” The “awed” tourists then listened as Mercier concluded, “He refused to outlive his glory and despised Napoleon for being so weak that he was willing to fall alive into the hands of his of his enemies. Our king took his own life, in one of the rooms of his palace [….] It was a proud ending.”

How to cite this essay: Marlene L. Daut, "Charles Lindbergh and Haiti’s Citadelle Laferrière, or the 'Eighth Wonder of the World'." King of Haiti's World Blog, February 13, 2026. <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/charles-lindbergh-and-haiti-s-citadelle-laferriere-or-the-eighth>