July 11, 1825 was a tragic day for Haiti: It was on this day that Haiti’s president Jean-Pierre Boyer "agreed" to pay an indemnity to France’s Charles X, amounting to 150 million francs, as the price of France's recognition of Haitian independence and to compensate the former French colonists for the loss of their “property.”

Ange René Armand, Baron de Mackau, the diplomat whom Louis XVIII’s brother and successor King Charles X sent to deliver the ultimatum (in the form of an ordinance dated April 17), had arrived in Haiti earlier that July, on the 3rd, aboard a frigate called La Circé. Although Mackau initially arrived with only two additional ships, he would eventually be accompanied by a squadron of 14 brigs of war carrying more than 500 cannons. After a few days of "conversation" with Haiti's president, Boyer signed the fatal agreement, which I wrote about for The Conversation here: “200 years ago, France extorted Haiti in one of history’s greatest heists – and Haitians want reparations” and for The Nation here in an article called "What the French Really Owe Haiti".

Pretty quickly after this, France’s king (with the help of his propagandists) began to paint himself as the historic liberator of Haiti, its veritable founder, and, perhaps even more shockingly, as a true lover of liberty. Keep in mind that slavery existed in France’s overseas territories (Martinique, Guadeloupe, Réunion, Guiana, etc.) for all of Charles X’s reign and for a long time afterward. Slavery would, in fact, not be abolished by the French until 1848.

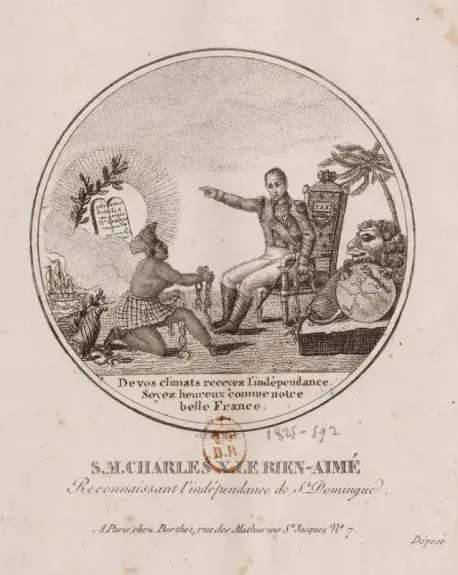

To give you some idea of the sheer force of French attempts to reshape the narrative about France's relationship to Haitian independence, in particular, and slavery's abolition, more generally, have a look at the 1825 engraving below. Like so many of the writings composed after the recognition treaty, this image attempts to depict Charles X as a benevolent liberator, with the French king appearing to bestow freedom on a Black man kneeling before him with broken chains.

French poet Nicolas Vigor-Renaudière’s poem, “The Haitian Canto,” first published in 1825, was even more egregious. The poem was a part of a vast discursive tradition in France that emerged after the 1825 indemnity agreement of celebrating Charles X as the true liberator of Haiti. But Vigor-Renaudière’s poem goes a step further than either the anonymously published “Ode to His Majesty Charles X, on the Emancipation of Saint-Domingue,” or Victor Chauvet’s “Haiti, Lyrical Song” (both can be found in my co-edited volume Haitian Revolutionary Fictions: An Anthology). “The Haitian Canto” not only falsely implies that slavery no longer exists anywhere in France because of the king’s belated recognition of Haitian independence but also states that Haitians should recognize how kindly the enslaved were treated under French slavery. Here are a couple excerpts:

Oh, Charles X, my King, whom I love and admire,

Haiti, this you know, the French were your fathers;

Yes, cruel at times, but sometimes good brothers . . .

Alas! There are blacks, who deep down surely know,

And will no doubt remember that even in their woe,

They were with us treated as part of the family;

Under the master’s roof their daughters found courtesy;

And very often also their emancipation

Was proof of the white man, the good master’s intentions:

Upon these freedmen then cloudless joy was bestowed:

Do you recognized yourselves in this tableau, good Negroes?

Over the hearts of the French, reign in all empire;

No, hear you no offense in the word liberty,

As you alone today, reclaimed its purity . . .

No more slavery, then, . . . all people become free;

Laws and the gracious prince ensure equity! . . .

And history will say a great and generous King,

Made none but happy men, the blacks emancipating.

Modern readers will no doubt chafe even more strongly at the poet’s blatant attempt to disregard the well-known fact of rampant sexual assault characteristic in all slaving societies by suggesting that enslavers always treated kindly the daughters of the enslaved.

With voluminous propaganda of this nature, the French attempted to congratulate themselves for supposedly paving the way for the destruction of the very system of slavery and colonialism that France helped to establish in the first place.

There is a lot more that could be said on this topic, and I am working on a few projects related to it. So, please stay tuned. Until then, Kenbe, pa lage.