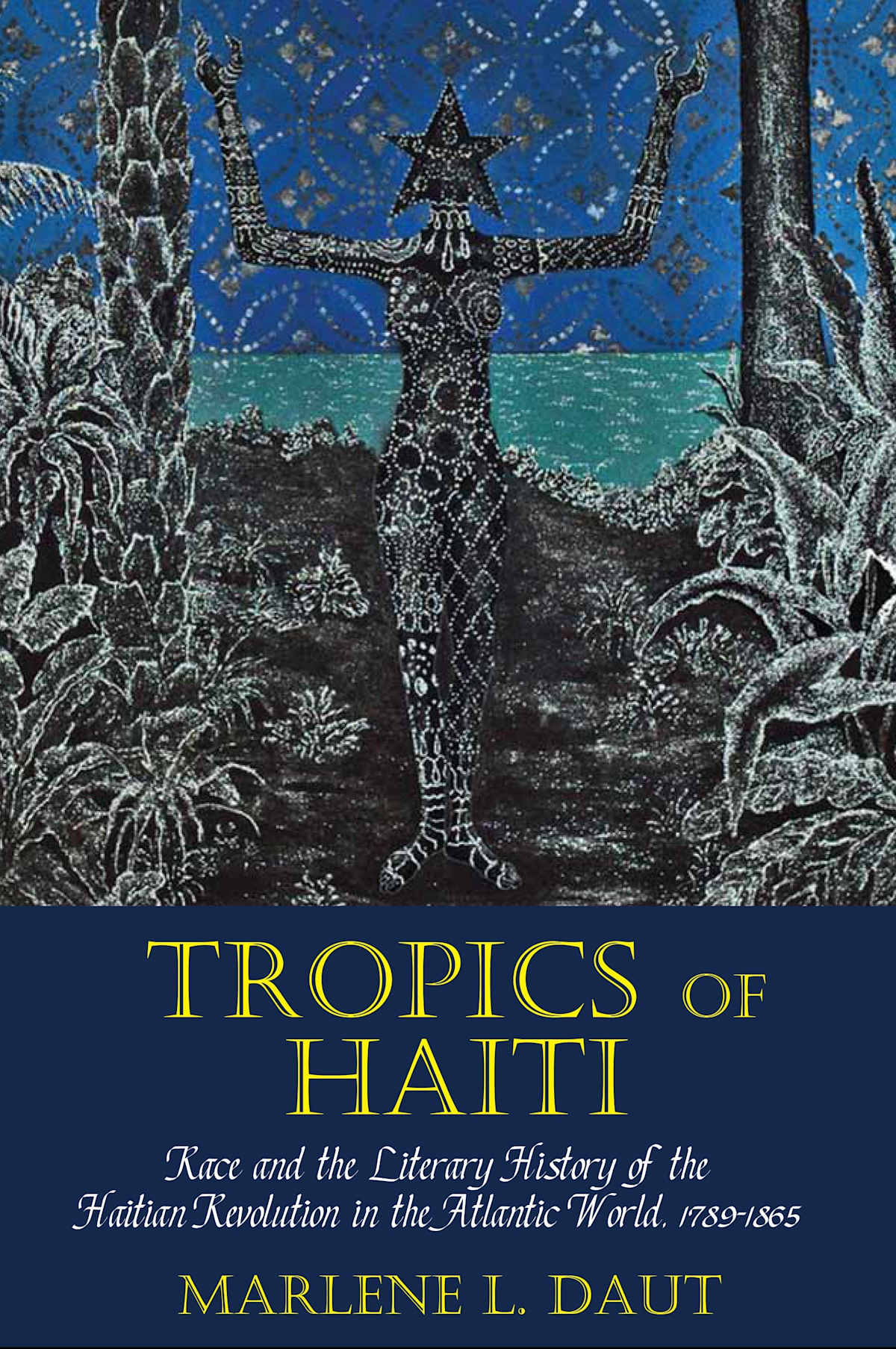

July 17, 2025 marks the ten-year anniversary of the publication of my very first book, Tropics of Haiti: Race and the Literary History of the Haitian Revolution in the Atlantic World, 1789-1865, published with Liverpool University Press on July 17, 2015. I can hardly believe it, especially since I was told by an editor at another press, who issued a blanket desk rejection, literally, five minutes after receiving an emailed proposal, that there was “no market for this.” The journey to publish this book was long and filled with boulders disguised as mountains. The key difference is that boulders can be moved—so, that is exactly what I did. I moved them. What follows below is a little bit of the journey that brought Tropics of Haiti to the world.

Exploring Fictions of the Haitian Revolution

I went to graduate school actually thinking that I would work on eighteenth- and nineteenth-century francophone poets from New Orleans, particularly those involved with a review called Les Cenelles. But in the process of learning about the history of francophone North American print culture, I came across a short story about a slave rebellion in French-claimed Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) by an author from New Orleans named Victor Séjour.

Séjour had emigrated to France, and in 1837 he published his first known work of fiction, "Le Mulâtre"—which, for a long time, was thought to be the first African American short story—in a famous Parisian journal called La Revue des colonies. This review, which was edited by the Martinican activist Cyrille Bissette, actually led me directly to nineteenth-century Haitian authors like Ignace Nau and Bauvais Lespinasse, whose fictional works appeared in the review as well. Encountering these francophone American and Haitian literary works in a Parisian review just made me want to delve even more deeply into what, at the time, were some very understudied authors, at least in the United States.

Because I was also reading more modern French Caribbean authors like Édouard Glissant, whose Faulkner, Mississippi was very formative for me, I was very aware of the importance of Haiti for US American literary genealogies, and the more I looked into it, the more I thought, this is what I really need to be studying. Then, when the coup d’état of 2004 happened, which unseated Haitian President Jean-Bertrand Aristide, my interest in nineteenth-century Haiti only took on more urgency.

Watching as disaster-focused narratives of Haiti continued to proliferate, it became even more important in my mind to continue to excavate the past precisely in order to be able to better understand the present. In so doing, I learned that Haitian historians, scholars, and writers of the nineteenth century were great excavators themselves, and their interpretations of Haitian history and Haitian politics are ultimately what I wanted to know and to read.

Yet, admittedly, my decision to take this path—focusing on nineteenth-century Haiti and including nineteenth-century Haitian authors—was much to the dismay of some of the professors in the English Department at the University of Notre Dame, who thought I should work on “canonical” authors who wrote only in English. I persisted on my own path anyway with the help of my very supportive advisors; and reader, I am happy to say that my persistence paid off. I was awarded my Ph.D. by the University of Notre Dame in 2009.

Afterward, I went from living in South Bend, Indiana, graduating with my doctorate in English (having written my dissertation on representations of the Haitian Revolution in 18th- and 19th-century French, Haitian, British, and US literature), to a job at the University of Miami, and then on to the Claremont Graduate University for seven years before settling in at the University of Virginia for six years.

I wrote about many of the biases and obstacles I faced during this time (boulders, again, not mountains), on my journey from graduate student to assistant to associate and then to full professor, in my article for The Chronicle of Higher Education: “Becoming Full Professor While Black.” But that’s not what I really want to talk about today. I’d rather reflect on the challenges and triumphs of writing my first book, which in some ways will always feel like my first intellectual baby.

"No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea"-Herman Melville

In English-language literary circles people often quote the famous statement made by Herman Melville's Ishmael from Moby Dick, “To produce a mighty book, you must choose a mighty theme. No great and enduring volume can ever be written on the flea, though many there be who have tried it.” One of the reasons Tropics of Haiti is so long (700-pages), and that the book took me so long to write (published six years post-doctorate), is because, the Haitian Revolution, as an event of monumental world-historical significance, generated thousands upon thousands of pages of writing.

As I show in the book, the Haitian Revolution not only impacted the world as it unfolded from 1791 to 1804, but it continued to have global resonance and international repercussions for decades after it was over, including upon the literary world. My argument in Tropics of Haiti concerns how pseudo-scientific debates about race, which were in their heyday at the time, wholly shaped the way that people thought and wrote about the Haitian Revolution in its era and for more than half a century afterward. The racialized ideas that people had about the Revolution were not insignificant because racist beliefs about Haiti shaped foreign policy (we can look to the works of Alfred Hunt, Tim Matthewson, Julia Gaffield, J. Michael Dash, Ron Johnson, etc. to learn more about this), and they also influenced the most intimate interactions between people—even members of the same family—which is what I try to show in the book.

But I knew that if I wanted to convince social historians that what people believed about the connection between race and the Haitian Revolution, whether in fictional or putatively non-fictional writings—namely, that it was free people of color and/or people of so-called mixed-race who were responsible for the Revolution’s onset (a very popular belief at the time)—was just as important as what actually happened—enslaved Africans, along with some former free people of color, overthrew white French enslavers and eventually the entire French plantocracy (a fact enslavers tried to occlude)—I would need a mountain of evidence.

It was not enough to simply show that in a few high-profile instances “mulattoes” were demonized in literary or historical works for allegedly having been the cause and motor of the Revolution, as for instance, in John Relly Beard’s Toussaint L’Ouverture (1853), Victor Hugo’s Bug-Jargal (1826), Lamartine’s Toussaint Louverture (1850), or Heinrich von Kleist’s “Betrothal in Saint-Domingue” (1811). I needed to show that claiming that the Revolution was an iteration of “mulatto/a vengeance,” and thus biological, rather than ideological, was a deliberate pattern that was as repetitive, extensive, and persistent as it was harmful, influential, and consequential.

So, I looked at biographies, histories, fictional writings of all kinds, personal letters, newspaper articles, codes of law, and even book reviews published up until the end of the US Civil War. I also read a lot of early modern pseudo-scientific theories about race, most of which derived from the seventeenth- and eighteenth-century French Atlantic World. In so doing, I recognized that an entire vocabulary had become attached to and was even developed around tying the Haitian Revolution and then Haitian independence to concepts like “monstrous hybridity,” stereotypes about both the “tropical temptress” and “tragic mulatto/a,” and then, just to finish off this form of “silencing,” ideas about blackness and mulattoness were also used to discredit Haitian historians themselves, which is what I referred to in the book as the phenomenon of the “colored historian.”

Researching for and then writing this book is one of the hardest things I have ever done. I think it was so hard because there was just so much that was unexpected. No one in my family has ever written a monograph, so I had to learn how to do everything from the jump, and I sometimes felt a bit lost. There was just so much material that had been written on the Haitian Revolution in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries (I have collected some of it in my co-edited anthology Haitian Revolutionary Fictions)—it was shocking, and I began to curse the day I ever got it into my head to write a literary history!

But once I started to really complete some chapters (there are twelve of them), I gained more confidence, and I was certain that I was going to finish. By that time, I was also determined that the world should know that the literary culture that sprung up around the Haitian Revolution was not insignificant or innocuous. Eighteenth- and nineteenth-century attempts to paint Haitian independence as the result of a racial revolution, rather than as the result of a desire for freedom from slavery and equality under the law, have helped render the Haitian Revolution insignificant and "unthinkable," in different forms, in both the past and the present.

I have to say that this research took me to some pretty ugly places. It’s hard to read racist words all day and not have it affect you. Many of the people who wrote about the Revolution in the early days, circa 1791 to 1803 (but sometimes after Haitian independence as well), were cruelly genocidal, which I wrote about in Tropics of Haiti, but also in this article for the Age of Revolutions blog: “Genocidal Imaginings in the Era of the Haitian Revolution.”

I drafted the bulk of this book from 2011 to 2013, and those two dates mark the birth years of my two sons. I jokingly said at the time that they were baby warriors to have survived the book writing days, because revolutions and wars, violence and virulent racism, were a huge part of what I thought about when I was carrying them. Yet, here we are, and here they are ten years later, all of us having lived through so many contemporary world-historical events already, and undoubtedly, with many more to come. We will get through it, is what I tell them. One day. For now, though, we must all try to be like our ancestors who fought and died so we could all be free; we must resist; and even if we can't, quite simply, we must do as so many before us could only do as well: hold tight, and don't let go.

P.S. The English Department at the University of Notre Dame recently asked me for a short reflection on my time there as a doctoral student, and this is what I told them: “The path of least resistance is not always the path to greatest fulfillment... Don't worry about the paths those around you are taking and definitely do not simply go where others have already tread, which is to say, do not fall into taking the safe route. There are too many different avenues waiting to be explored to simply follow the herd.”

P.P.S. I also received belated, but truly welcome, recognition of my accomplishments as a writer, educator, and public scholar when in January 2023 the Alumni Association of Notre Dame awarded me The Rev. Robert F. Griffin, C.S.C., Award for Outstanding Accomplishments in Writing. Better late than never, pa vre?

To cite this article: Marlene L. Daut, "10th Anniversary of 'Tropics of Haiti': Reflections on a First Book," King of Haiti's World Blog, July 17, 2025 <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/10th-anniversary-of-tropics-of-haiti-reflections-on-a-first-book-july>