By Marlene L. Daut

This week marked a historic day of teaching for me. Along with my colleague Professor Kaiama Glover, we launched a two-semester course, "Haiti Writes I" and "Haiti Writes II." After a search through institutional course records at Yale, Kaiama confirmed that our class is the first at the university to be devoted solely and entirely to Haitian literature. For me, this is both a moment to be celebrated and one to be pondered.

Putting aside for now the deep historical, cultural, and political ties that link Haiti to the United States—and the fact that Connecticut has a robust Haitian American population that I am proud to be a part of—Haitian literature is and has been for a long time renowned and admired around the world.

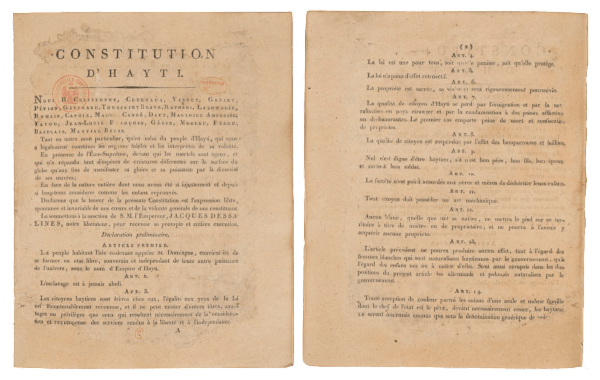

So robust was the print culture of independent Haiti in the first two decades of its existence that by 1819 Haitian literature had already been recognized as its own national genre. In a two-part article called “De la littérature haïtienne” (On Haitian Literature) published in the Revue encyclopédique out of Paris in 1819, French critic and historian Antoine Métral described in meticulous detail the tremendous scope of early Haitian letters. Evoking Dessalines’s and Christophe’s constitutions, along with the writing of Juste Chanlatte, Jules Solime Milscent, François Desrivières Chanlatte (brother of Juste), and Baron de Vastey, among others, Métral characterized the prolific literary output of Haitian authors as filled with “sublime ideas of poetry and eloquence,” which he said, “delve deeply into the most profound abstractions of metaphysics.”

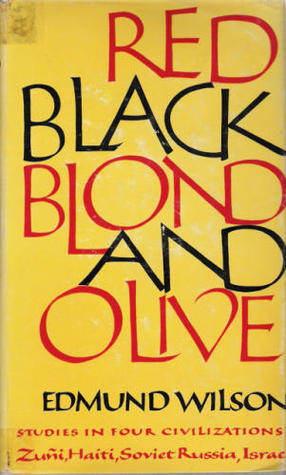

Fast forward to the twentieth century, and in 1956, after an extensive sojourn in Haiti, the U.S. writer and literary critic Edmund Wilson could not help but to marvel as well. “The literature of Haiti,” Wilson wrote, “is highly sophisticated and has a long and sound tradition behind it. It is surprising to learn that this island, since the revolution of 1804, has produced a greater number of books in proportion to the population than any other American country, with the exception of the United States.”

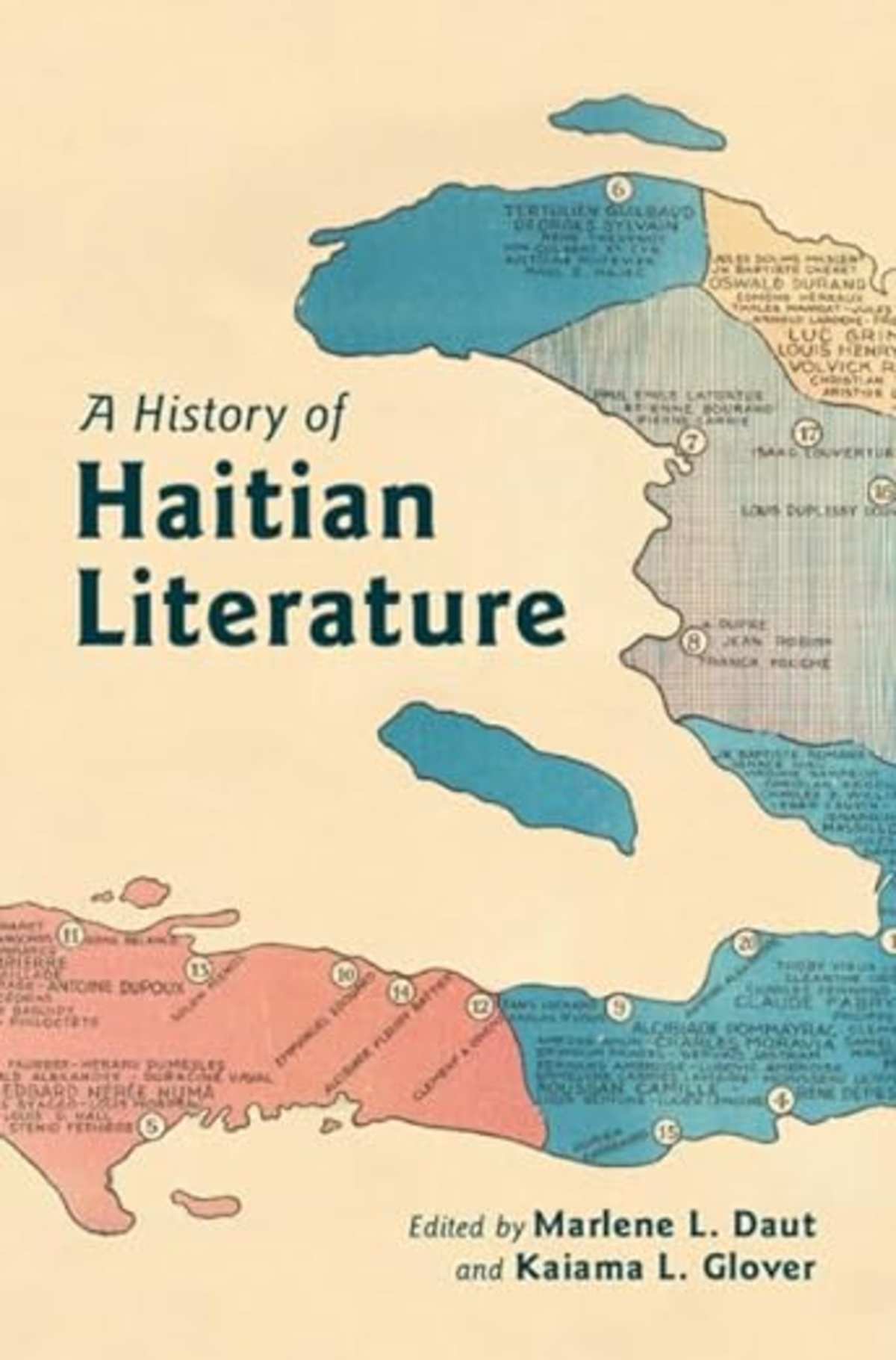

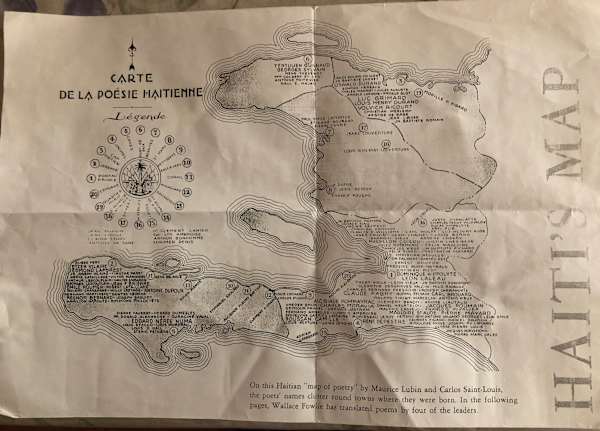

I have been studying Haiti’s robust and longstanding literary culture for more than twenty years. And I have devoted a large part of my scholarly life to making early Haitian literature (18th and 19th century) available to as wide an audience as possible. (Check out my digital humanities project, La Gazette Royale d’Hayti: A Digital Journal Through Haiti’s Print Culture and co-edited volume Anthologie de la pensée noire, for just two examples.) The same prolonged study of the longue durée of Haitian literature is the primary object of the edited volume that Kaiama and I recently published with Cambridge University Press, A History of Haitian Literature. In fact, we developed our course description in large part based on the contents of the volume:

“From 19th-century antislavery pamphleteering to accounts of ecological catastrophe in 21st-century fiction, Haitian literature has resounded across the globe since the nation's revolutionaries declared independence in 1804. Starting with pre-revolutionary writing, including the emergence of Haitian Creole letters, moving through a long, largely francophone nineteenth century to present-day Haitian writing in the English language, this two-semester exploration of Haitian literature presents the political, cultural, and historical frameworks necessary to comprehend Haiti's vast literary output. Whether writing in Haiti or its wide-ranging diasporas, Haitian authors have boldly contributed to pressing conversations in global letters while reflecting Haiti's unique cultural and historical experiences. Considering an expansive array of poets, playwrights, and novelists—such as Baron de Vastey, Juste Chanlatte, Demesvar Delorme, Edwidge Danticat, René Depestre, Kettly Mars, Dany Laferrière, Évelyne Trouillot, and others—this course engages students in a fresh examination of Haiti’s richly polyglot and transnational literary tradition that spans more than two centuries.”

I came to Yale precisely to have the opportunity to develop new courses that would not require me to be beholden to what was already in the course catalog or to the “canons” that the institution’s predecessors decided most deserved to be included on the syllabus. I am happy to say that my courses on Haiti at Yale, like my courses on the Caribbean, in general, have consistently had high and even over enrollment.

In my experience, students are hungry to learn about Haiti and the broader Caribbean, and by the time they get to my courses, they often wonder how it is that they should know so little about a country and a region that is so crucial to understanding our modern world. After all, the Caribbean islands were the first to be colonized and enslaved in the Americas, and Haiti was the first modern state to permanently abolish slavery.

In fall 2024, I had the opportunity to teach the first class on Yale uniquely devoted to the Haitian Revolution: "Haiti in the Age of Revolutions." I was extremely gratified when C-Span noticed the historic occasion and stopped by on December 11, 2024, to film the final course session: the program aired in early 2025 under the title, “Henry Christophe and the 1791 Revolution.” Now that we have brought Haitian literary studies, as such, to Yale, I can’t help but to feel that this occasion needs to be marked, too.

There is a lot that the world can learn from Haitian thought, if they’d only give something unfamiliar, but of critical importance, the old college try. As we wrote in the introduction to A History of Haitian Literature, by studying Haitian poets, novelists, and playwrights, along with the country’s essayists, anthologists, and literary critics, our aim is to “present a hopeful counter to the limiting stereotypes that naysayers have attached to Haiti and its people over the course of the nation’s history” and to “offer greater insight into Haiti’s extraordinary literary tradition while expanding the foundation of the growing field of Haitian Studies.”

How to cite this article: Marlene L. Daut, "A Historic Day of Teaching at Yale," King of Haiti's World Blog, September 4, 2025. <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/a-historic-day-of-teaching-the-first-haitian-literature-class-at-yale-by>