Resistance and Fugitivity on the Island of Saint-Domingue

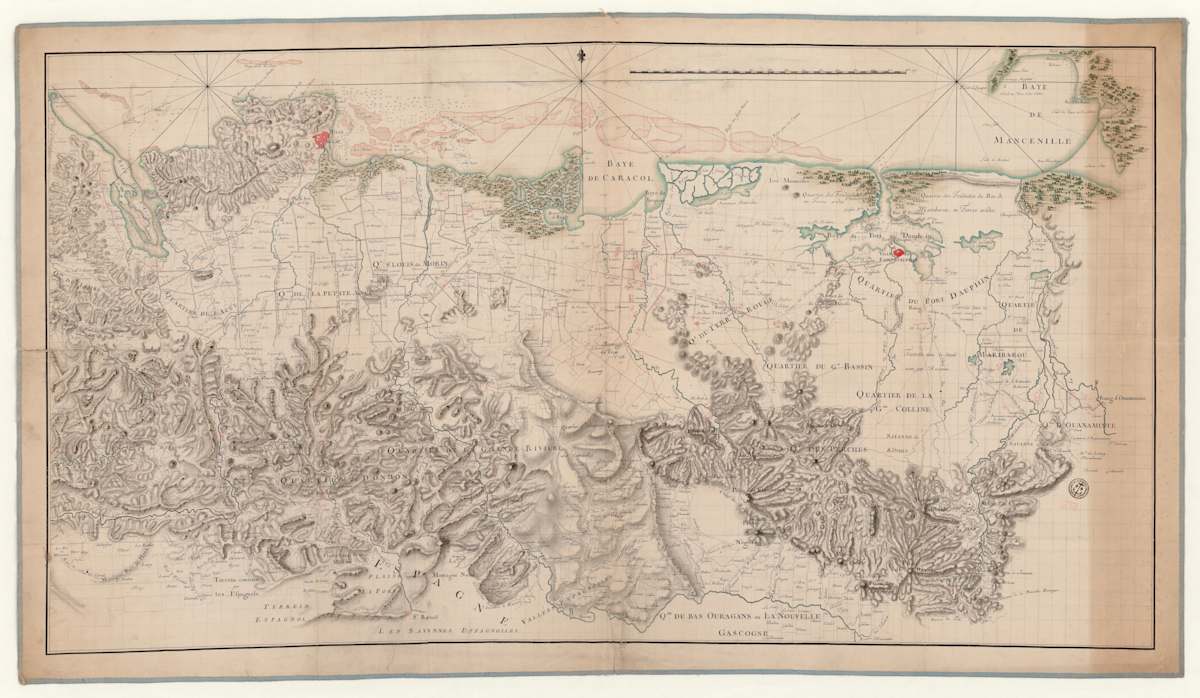

On December 1, 1773, a 22-year-old enslaved man, about five-feet tall and originally from South Africa, was captured by French authorities in Petit-Goâve, on the island of Saint-Domingue, a French colony at the time. The captive had run away from the man who had enslaved him to become a maroon, or a fugitive from slavery. Upon his capture, when the jailer asked for his name, the man, who spoke no French, said likely the only word he knew, “liberté,” or liberty. The jailer then foolishly recorded his captive’s name as Liberty. This was cruel irony. The poor captive couldn’t have been further from freedom.

An enslaved person had few ways to control their own life, or that of their children, and enslavers used violence every day, in ways big and small, to prevent the people they enslaved from exercising any will. Yet the enslaved of Saint-Domingue heavily resisted their enslavers' cruelty every day too. In the town of Mirebalais, for example, a colonist named Denis burned the feet of one of the women he enslaved, the 38-year-old Marie-Jeanne, called Grande Jeanne. To prevent experiencing this torture again, she ran away.

Also called marronnage, this was common on the island and spanned all ages. In October 1780, 26-year-old Sans-Souci with his hands maimed, likely from working at the sugar mill, deserted the plantation in Gonaïves where he had been forced to labor by a Mr. Genève; and that same month, 32-year-old Baptiste, 27-year-old Marie, and 11-year-old Marie-Louise, a whole family enslaved in Petit-Trou, disappeared into the woods to escape from slavery.

Yet solo marronnage was far more common, even for children. In September of that same year a young ten-year old boy named Henri, like a twelve-year-old girl called Pélagie before him, braved the wilderness of the island’s mountains alone, in hopes of ending the tortures of slavery. And imagine the terrors and tortures ten or eleven-year-old Marie-Noël must have survived to have preferred facing nature, with no adult wisdom to carry her through, when, in May 1785, she took off on her own from her enslaver, the appropriately named Villain Baron.

It is astonishing to learn that even younger children like Marie-Louise, who was only 5 or 6 years old when she left her enslaver’s house in the colony’s sleepy capital of Port-au-Prince, faced the hills alone, risking almost certain death. Even a child could tell that there was a great difference between slavery and freedom. Like Marie-Louise and thousands of other enslaved Africans, men, women, and children— the maroons of Saint-Domingue—consistently and repeatedly tried to liberate themselves.

Marronnage was dangerous business regardless of age, however. Enslavers on Saint-Domingue, France’s richest colony in the 18th century, punished enslaved people who ran away by burning and burying them alive, severing their limbs, ears, and other body parts, bleeding them to death, or nailing them to walls and trees. Enslavers also routinely subjected the people they enslaved to branding (stamping an enslaver’s name on a body with hot irons) and other mutilations meant to prove ownership.

If an enslaved person had more than one “owner” over the course of their life, they could have multiple stamps scarring their body. When an enslaver named Lataille purchased a captive African man in May 1781 he added his name to the two others already crudely burned onto the man’s body: GAULON on one breast, GARNIE on the other, and above that D. LATAILLE.

Sometimes, the cruel colonists used the stamps to exert their authority or send a message. This was the case with a man from Senegal named Jean-Pierre, enslaved in the Artibonite valley by one of the most infamously evil men in the colony, Mr. Caradeux. Stamped on Jean-Pierre’s right breast were the words of his enslaver and torturer, CARADEUX, but stamped on his left shoulder were the words, “JE SUIS MARON,” or I am a maroon.

In a world of slavery, not youth, old age, gender, or disability could offer protection from the unbelievable terrors of the slave auction block where enslaved people were sold to the highest bidder. Poor Marie-Joseph Fanchon was forced to have the child of her enslaver, Victor Bernier, just before he sold her; while a Madame Allard put up for a sale one of the women she enslaved just twelve days after the woman gave birth to a baby, advertising her as a “good wet nurse” who knows how to sew and go to market. Even an elderly blind man could find himself up for sale, as in the case of a man enslaved by the colonist Galtier who said that despite his lack of sight, the man could still turn the wheel to produce the commodity that mattered more than Black lives to the colonists of Saint-Domingue: sugar.

Although their spirits may have been bent, the constant resistance of the enslaved showed that even the worst cruelties could not entirely break them. While a captive African’s body could perhaps remain enslaved in perpetuity by the white colonists, their repeated fugitivity suggests their minds never could.

To cite: Marlene L. Daut, "A Slave Named Liberty; or, 'I am a Maroon'," King of Haiti's World blog, March 13, 2025. <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/a-slave-named-liberty-or-i-am-a-maroon-resistance-and-fugitivity-on-the>

Cross-posted at Medium: https://medium.com/@marlenedaut/a-slave-named-liberty-or-i-am-a-maroon-4130bd34d10d