What writing about Haiti’s first, last, and only king taught me about archives, ethics, and unreliable narrators.

By Marlene L. Daut

As a literary and intellectual historian, I have spent a large part of my career focusing on how literary fictions (poetry, drama, novels, and short stories) affected the way that people living in the 18th and 19th centuries understood the Haitian Revolution (1791-1804). My newest book, a biography called The First and Last King of Haiti: The Rise and Fall of Henry Christophe (Knopf, January 2025), therefore might seem like a true divergence from my prior writing.

In The First and Last King of Haiti I pursue what is in some ways a fairly traditional cradle to grave biography. Yet something a little bit untraditional is that I have also produced a work of historiography in that I take the reader behind the scenes and let them know what all the conflicting accounts about Henry Christophe say (for example, about his place of birth), often times holding back judgment, since in many cases it is impossible to make an objective determination.

I also further elaborate on Christophe’s radical influence over Haitian revolutionary and post-revolutionary political ideas—indeed, his two most prominent secretaries, Juste Chanlatte and Baron de Vastey, published under the state press created by Christophe to combat racist and stereotypical portrayals of Haiti, on the one hand, and to spread anti-slavery, anti-racist, and anti-colonial ideals across the world, on the other.

Instead of focusing on his life, I could have turned to discussing fictional representations of Christophe, which are legion and mostly reflect demonization of him—which I think would be a very interesting project. In fact, I begin the biography with a prologue that has a highly literary quality to it, in that I discuss the many, many attempts to portray Christophe’s life on the page and the stage from the nineteenth century to the present.

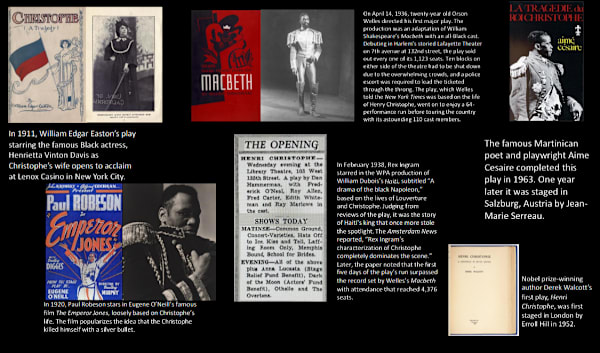

I take readers from British author J.H. Amherst’s Christophe, King of Hayti, staged in London’s Coburg Theatre throughout the 1820s, to the Black playwright William Edgar Easton’s Christophe, a Tragedy (1911), which starred Henrietta Vinton Davis (she played an avenging priestess and basically stole the show), to Rex Ingram’s portrayal of the Haitian king in William Dubois’s Haiti: A Drama of the Black Napoleon, to Orson Welles’s 1936 staging of Macbeth with an all-Black cast (which Welles says was inspired by Christophe’s life, and which earned the production the nickname “Voodoo Macbeth”), to more recent attempts to stage his life by Derek Walcott (1949) and Aimé Césaire (1963).

Of course, the author who most infamously tried to fictionalize Christophe’s life was the Swiss-born Cuban author Alejo Carpentier, whose highly popular novel The Kingdom of this World (originally published in Spanish in 1949) has led to a generation of people who continue to encounter Christophe’s story, but who often seem to confuse fiction for history after reading Carpentier’s completely invented portrait of the Haitian king. Combining marvelous realism with apocryphal legend (largely based on dubious 19th-century foreign accounts), Carpentier paints Christophe as “a monarch of incredible exploits” who everyday ordered “several bulls” to have “their throats cut so that their blood could be added to the mortar to make [his] fortress impregnable.”

But what I try to make clear to readers at the outset of the book by first introducing them to the vast fictional corpus of representations of Christophe—one that also includes John Vandercook’s Black Majesty (1928) and a 1983 Mexican comic book inspired by it and distributed all over Latin America, Fuego: Majestad negra—is that if we hope to understand Christophe’s life and death, we must ultimately turn away from the fictional portrayals. The tendency of historians and artists alike to portray Christophe as an irredeemable monster and his downfall as ultimately inevitable has obscured the intricate personal and political events that led to his dramatic demise, rendering him one of the least understood heads of state in the Americas.

Influenced by the ideas of Arlette Farge in The Allure of the Archives, I felt a responsibility to try to understand Christophe beyond caricature and cliché, as a real human person, who was not larger than life. And as I combed through pages and pages of correspondence, birth and death registers, newspapers published in multiple countries and multiple languages, I became acutely aware that in my retelling of this life, I had a responsibility to my subjects, even though they are all deceased. For, as Farge states, “lives are not novels, and for those who have chosen to write history, the stakes are not fictional.”

I wanted to get to the heart of Christophe’s experiences as a child and as a revolutionary, to his role as a father, a husband, and a friend, and ultimately, to the complicated story of how he became king. This meant consulting the numerous forms of writing he left behind and those of his family, his friends, and even his enemies and political rivals.

At the end of the day, perhaps what I most learned by entering into this new genre, is that writing a biography involves process as much as ethics. I think there can be a temptation when writing from the perspective of someone’s life, especially if they lived a long time ago, for the biographer to become the person who gets to decide what is true and what is not. I think the more a historical figure has been demonized or caricatured, the stronger the temptation becomes to appear as such an all-knowing (and even righteous) decider. The biographer in that case might decide to write more positively about the person or might try to prove that all the negativity is warranted. I think both of those impulses are dangerous.

In The First and Last King of Haiti, I opted to take the role of investigator. In fact, I have found myself often using the term “investigative historicism,” drawn from the idea of investigative journalism. While writing and researching for this biography I read a lot of different kinds of non-fiction. I was reading The Immortal Life of Henrietta Lacks by Rebecca Skloot and Ariel Sabar’s Veritas: A Harvard Professor, a Con Man and the Gospel of Jesus’ Wife, for instance. These are both superbly written works of investigative journalism, from which I learned a lot about how to weigh a massive amount of evidence when many, if not all, the stories conflict with one another. What kinds of conclusion should a researcher draw from conflicting accounts? How do we talk about unreliable narrators? And what do we do with the outright liars, whose accounts have nevertheless influenced public opinion? It’s all good and well to debunk a lie, but as a writer, you must also convince people that what they previously believed was, according to the evidence, not really the truth; otherwise, they’ll think you, as the newest biographer on the street, are the one who is wrong.

I eventually came to the realization that telling the story of Christophe’s life in a completely straightforward way—where the author decides behind the scenes which accounts are most reliable based on factors not disclosed to the reader—was not going to be possible without doing a lot of harm to history and therefore to understandings of Christophe’s biography in the process. Mine would then just become one more account among a vast array of other accounts; that is, one more node in a long list of possibilities, i.e. Christophe was born in St. Kitts, or St. Thomas, or Grenada, to take a simple and the most obvious example. To get the reader to understand and accept that the best evidence available points to Christophe's birth in Grenada, I had to first and at the outset acknowledge those other accounts about his birthplace, explain where those stories came from, and tell the reader why I believe those chroniclers were incorrect—hint: the accounts of his life saying he was born in Grenada came from writings Christophe commissioned and published in his own kingdom during his reign and therefore amount to a form of self-testimony.

I eventually became comfortable with the idea that I had to acknowledge point of view all the way through the tale, even in a narrative history written for a popular audience, and more importantly, I had to accept that we may never know the truth. This is, in fact, true of every life, even if someone has written their own autobiography. You will find accounts that contradict what someone says about their own life because people’s memories differ, and their interpretation of those memories differ even more so.

Neither hagiography nor villainization, neither lionization nor an apology, in The First and Last King of Haiti I take readers through the twisting and winding fate of a man most likely enslaved at birth, separated from his mother at a young age, who participated in two revolutions—the American Revolution at the Battle of Savannah at age twelve and the Haitian Revolution as a grown man in the 1790s—and whose wholly unlikely path to leadership led him to have it all and then lose it all.

A lot of things had to happen to create the circumstances for Christophe to become Haiti’s first and last king—the man who oversaw construction of Haiti’s famous Citadelle Laferrière, a UNESCO World Heritage Site and the largest fortress in North America, widely hailed as “the eighth wonder of the world”—but to get to those stories, I invite you to read the book.

How to cite this article: Marlene L. Daut, "Behind the Scenes of a Revolutionary Biography," King of Haiti's World Blog, June 10, 2025 <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/behind-the-scenes-of-a-revolutionary-biography-what-writing-about-haiti-s>