BY MARLENE L. DAUT

“If injustice, bad faith, and cruelties of all kinds, give rights to those who have experienced them, over those who have perpetrated them, what people have ever had more right to independence than the Haitian people?”—BARON DE VASTEY, Réflexions sur une lettre de Mazères (1816)

In the April 22, 1922 edition of the famous Harlem Renaissance era magazine, The Negro World, Eric Walrond recalled a visit he made to the Puerto Rican American bibliophile, collector, and scholar Arturo Schomburg’s library in New York City. Walrond, who was accompanied by then graduate student Zora Neale Hurston, described Schomburg’s excitement as he presented several rare books and other documents before his young visitors. Among those texts was Baron de Vastey’s Le Cri de la Patrie (1815), a pamphlet whose title Schomburg translated as “Cry of the Fatherland in the Interest of All Haytians,” and which Walrond called, “of course a very valuable work.”

Later, in his celebrated 1925 essay, “The Negro Digs up his Past,” Schomburg wrote that Baron de Vastey’s Cry of the Fatherland, “the famous polemic by the secretary of Christophe,” formed a part of a larger body of writing by diasporic Black Americans so impressive as to form “evidence[…] of scholarship and prowess” “too weighty to be dismissed as exceptional.”

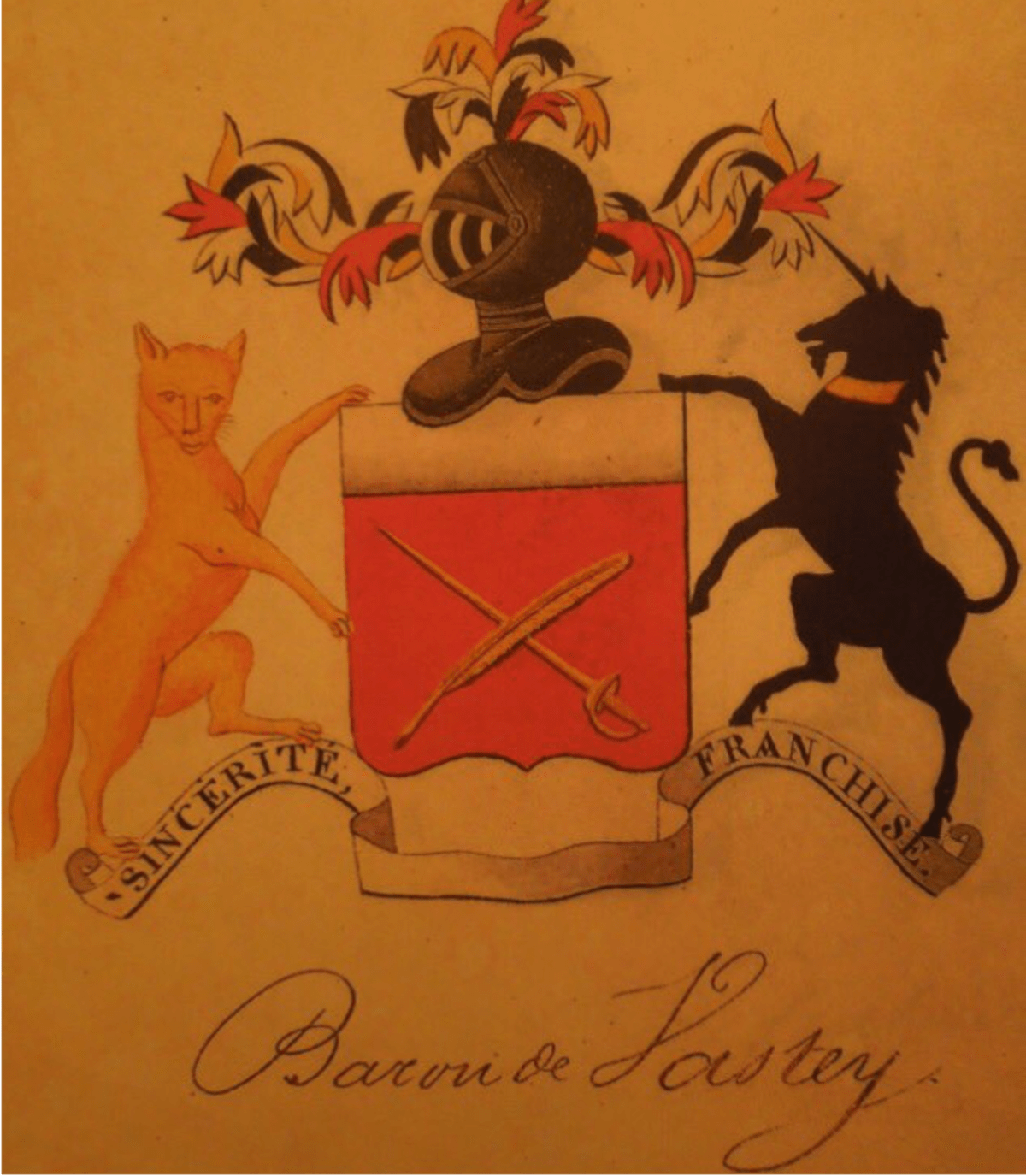

The man who so fascinated Schomburg, and other Black U.S. writers of the early twentieth century like W.E.B. Du Bois and Alain Locke, was Baron de Vastey (January 21, 1781-October 18, 1820), born Jean-Louis Vastey in the city of Ennery in colonial Saint-Domingue to a white French father from Normandy and free woman of color from Marmelade.

A celebrated writer in his own era, too, as one of King Henry Christophe’s most important secretaries, Vastey published at least eleven book-length prose works within a span of only five years (1814-1819); and his works gained immediate traction, as he was often favorably compared to two more well-known Anglophone writers from the African diaspora, Phillis Wheatley (c. 1753-84) and Ignatius Sancho (c. 1729-1780).

In fact, although he is largely unknown outside of academic circles today—and as Schomburg’s utmost veneration illustrates—Vastey has historically been an icon of the African diaspora. As stated in the 1971 Annual Report of the Library Company of Philadelphia, which had recently acquired several of his works, Vastey should be considered “a pioneer […] in positive black thinking,” who, “probably [produced] the first scholarly, serious socio-ethnological study by a Negro.”

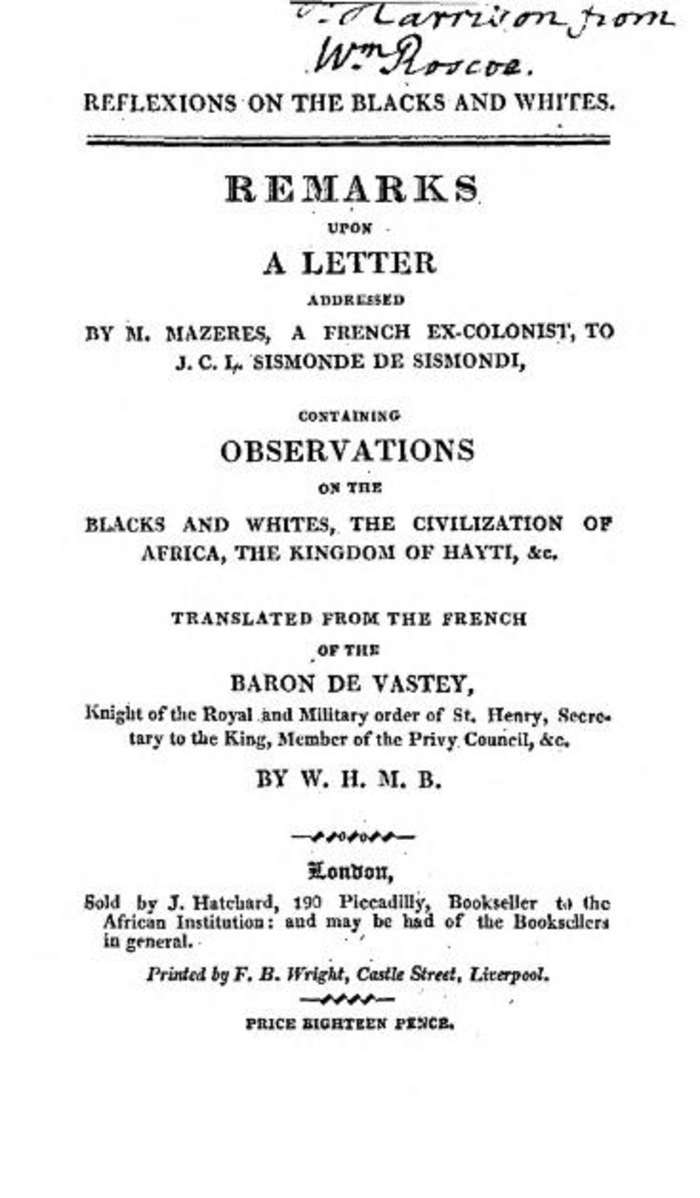

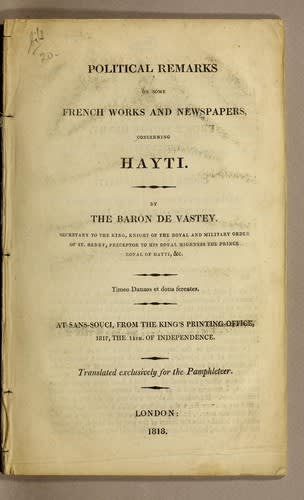

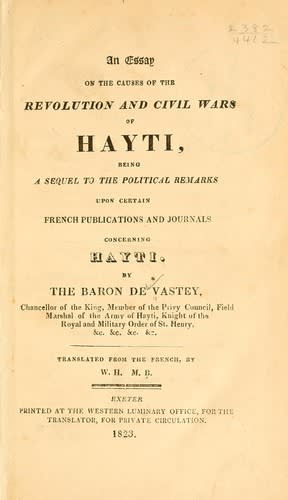

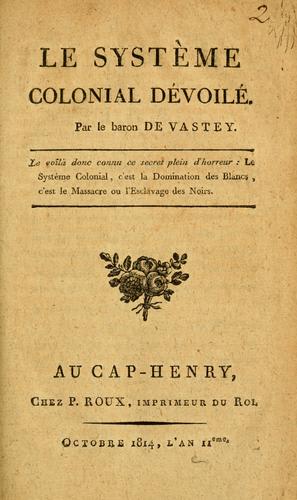

It is not just Black writers who have historically been interested in Vastey’s oeuvre, however. Vastey’s most damning exposé of the inhumanity of the colonial system in what is today his most celebrated work, Le Système colonial dévoilé (1814), was of such intrigue at the time of its initial publication that it was immediately reviewed in French, US, German, and British journals and newspapers. By 1823 at least four of Vastey’s subsequent works had even been fully translated into Dutch and English, with a few excerpts also appearing in Italian, suggesting that Vastey’s keen dismantling of pro-slavery writing had a global appeal to nineteenth-century readers and publishers.

(Title page of 1817 English translation of Baron de Vastey's Réflexions sur une lettre de Mazères, originally published in 1816)

(Title page of 1818 English translation of Baron de Vastey's Réflexions politiques sur quelques ouvrages et journaux français concernant Hayti, originally published in 1817)

(Title page of 1823 English translation of Baron de Vastey's Essai sur les causes de la révolution et des guerres civiles d'Hayti, originally published in 1819 and the first full-length history of Haiti written by a Haitian)

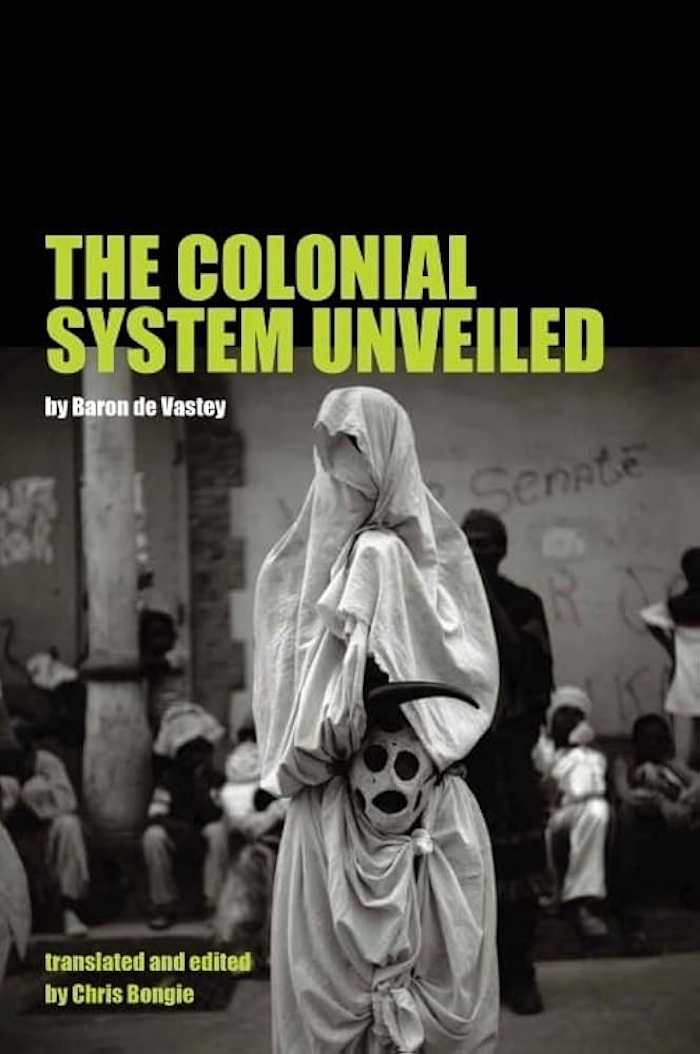

Yet it remains telling that despite its broad transatlantic circulation, and even popularity, Le Systeme colonial dévoilé—Vastey’s most concrete testimony of the inhumanity of colonialism and slavery—was never fully translated into any language in his own era and that it took 200 years for it to appear in English translation in our own. The catalog of abuses Vastey records, while providing the exact names of the guilty colonists and their unfortunate victims, seems to me in large part responsible for the tardiness of the translation.

(Cover of 2014 English translation of Baron de Vastey's The Colonial System Unveiled, translated by Chris Bongie for Liverpool University Press)

In this slim volume, Vastey catalogued more than 100 forms of torture perpetrated by the French colonists of Saint-Domingue against the people they had enslaved. Vastey also lambasted the already voluminous writings on the Haitian Revolution produced in Western Europe and the United States, whose authors decried the violence of the enslaved freedom fighters during the Revolution while silencing the inherent violence of slavery itself.

Indeed, Vastey stated that his goal in producing this work was to “unveil the heinous crimes” of the French colonists by consulting the dead to share their stories from the grave. Vastey declared that bringing to light these damning testimonies against enslavers required him to “awaken the ashes” of the “numerous victims” whom the colonists “precipitated into the tomb” and “borrow their voices.” By awakening these ashes (the quote from whence I derived the title of my 2023 intellectual history of the Haitian Revolution), Vastey offered to tell the history of colonial slavery, and its many brutalities, from a Haitian perspective using a strategy today’s historians might recognize as “history from below.”

In Vastey’s writing, awakening the ashes is not just a metaphor. Some of the testimony came from below the ground. Vastey insisted that death was not an obstacle to accessing the experience of the deceased. Yet he also had living witnesses. Vastey not only detailed his interviews with the still alive victims of slavery, but he spoke of incorporating the testimonies produced by their mutilated limbs and scars, as remnants of the tortures these victims had experienced. In so doing, Vastey’s goal was to produce a collective history of the enslaved population of colonial Saint-Domingue, one drawn from their own perspective—a not at all common method in the Atlantic World of his time.

It remains wonderous to me that Vastey was writing a “history from below” in the early nineteenth century when that phrase would not be popularized until 1966 when the British historian E.P. Thompson used it as the title of his famous essay published in The Times Literary Supplement. Nevertheless, it is Vastey's book that is far more crucial to imagining anew how we should talk about, theorize, and comprehend the role of lived-memory in history writing.

When Vastey published Le Système colonial dévoilé , Haiti had only been independent for 10 years. The memory of slavery was fresh and extremely vivid for those who had lived through it. Part of what Vastey is doing in this work is to say that just because Haitians had definitively abolished slavery in their country, this did not mean that the formerly enslaved or their ancestors had forgotten what they suffered at the hands of the French. How long would it take them to forget? Would their dead ancestors want them to forget? These are questions that Vastey grappled with as he tried to write a subaltern history of slavery and then of Haiti that would oppose the dominant, colonial perspective surging through European writings about the events of the Haitian Revolution and Haitian independence.

I think today’s scholars are still struggling to fully realize and/or replicate the kind of methodology Vastey employed. Which is to say, how do we talk to the dead rather than solely about them?

How to cite this essay: Marlene L. Daut, "OTD in Haitian History (January 21, 1781): Birth of Haiti’s most prominent anti-slavery and anti-colonial thinker, Baron de Vastey," King of Haiti’s World Blog, January 21, 2026. <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/otd-in-haitian-history-january-21-1781-birth-of-haiti-s-most-prominent>

***Parts of this post appear in modified form in Awakening the Ashes and in this 2018 interview I did with Julia Gaffield for Black Perspectives about my book Baron de Vastey and the Origins of Black Atlantic Humanism (Palgrave Macmillan, 2017). I present more information about Schomburg and his collecting practices vis-à-vis the Kingdom of Haiti in my forthcoming essay, “Arturo Schomburg Digs up the Kingdom of Haiti’s Past,” in Black Studies on 135th Street, ed. Barrye Brown, Laura Helton, and Vanessa K. Valdez (Yale University Press, April 2026).