By Marlene L. Daut

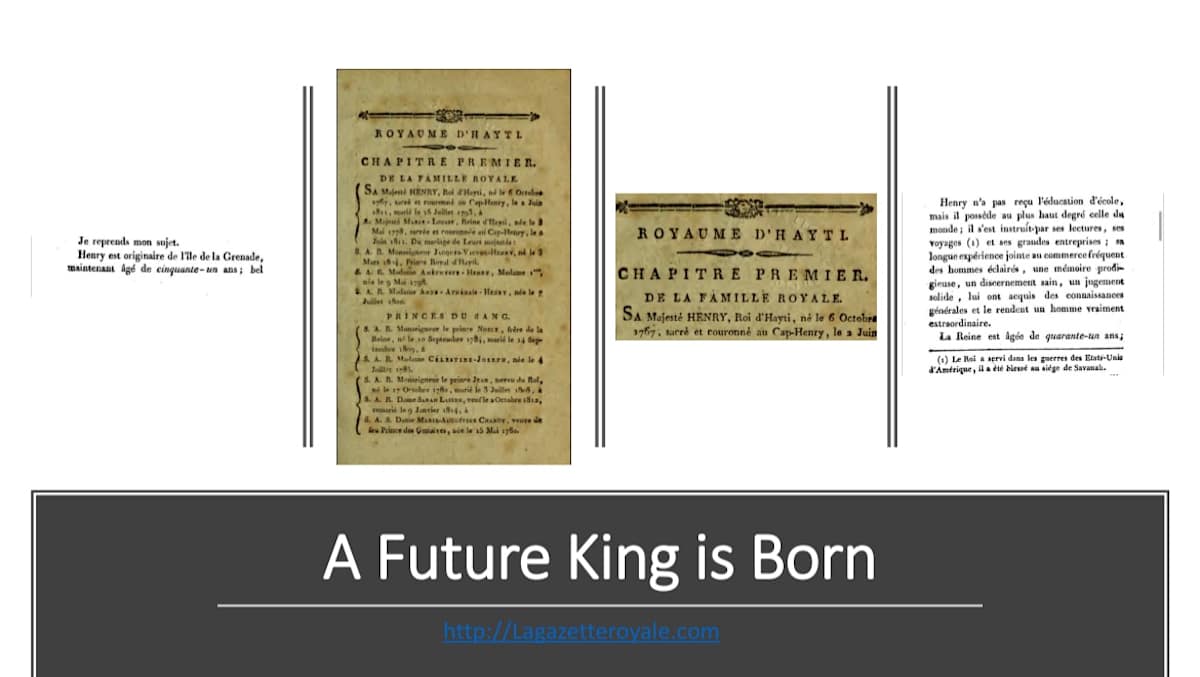

For a long time, historians disagreed about the origins of Haiti’s first and only king, Henry Christophe. Yet in my recently published biography, The First and Last King of Haiti, I tried to close the case by first pointing out that in the six different versions of the Almanach royal d’Hayti, published out of the royal press of Haiti from 1814 to 1820—and hailed by bibliographer Ralph T. Esterquest as the “Burke’s peerage for Christophe’s grandiose kingdom”—the king’s date of birth is definitively listed as October 6, 1767.

Similarly, although some say Christophe was born on the island of St. Kitts, three men who had been, at various times, in his inner circle—Hugh Cathcart, a British agent at Port-Républicain (Port-au-Prince); Colonel Vincent, a French military officer; and Baron de Vastey, secretary to the king—report that Christophe was born on the British island of Grenada. Vastey’s Essay on the Causes of the Revolution and Civil Wars of Hayti (1819) is the most significant of these accounts: it is the only one we know that Christophe not only read, but commissioned, and therefore, sanctioned.

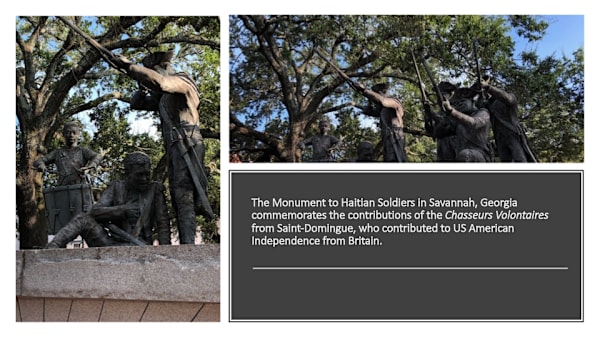

According to Vastey, Christophe, aged 12, also fought in the Battle of Savannah during the American revolutionary war on behalf of the American colonists with the French Chasseurs Volontaires, a regiment of troops of color from the French colonies. By the time full-scale slave rebellion broke out in the French colony of Saint-Domingue in August 1791, Christophe found himself employed on the island at the Hôtel de la Couronne on rue Espagnole in Cap-Français.

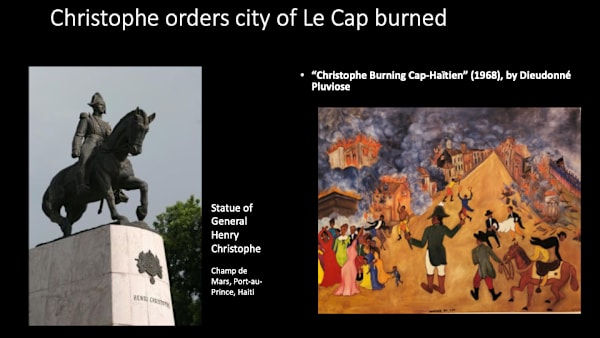

Fighting alongside the famous General Toussaint Louverture, Christophe helped force emancipation of Saint-Domingue’s enslaved population in 1793. The French revolutionary government then abolished slavery throughout the French empire in 1794. However, by 1799, Napoléon Bonaparte had risen to power in France and insisted on restoring slavery. When he sent his brother-in-law General Leclerc to Saint-Domingue for that purpose with 30,000 French troops in early 1802, the French found brigadier-general Christophe, commander over the city of Le Cap, stern, stoic and inflexible. Christophe eventually had the city burned to the ground to prevent French military invasion.

But at the end of April 1802, convinced by Leclerc that the French had no intention of reinstating slavery, Christophe briefly defected to the French side, which inadvertently helped lead to the demise of the great revolutionary general Toussaint Louverture. Not long after, most of Louverture’s allies also defected, and the French subsequently arrested and deported Louverture to France where they left him to die a cold and miserable death in prison.

After news reached Saint-Domingue that Bonaparte had reinstated slavery in Guadeloupe, Christophe abandoned the French military and became a key member of the indigenous army that eventually freed Haiti. However, wary of the fact that Christophe had previously fought on the French side, rival Colonel Jean-Baptiste Sans-Souci refused to accept Christophe’s re-integration. In retaliation, Christophe had him executed. This execution has clouded Christophe’s legacy—even if, relatively speaking, it was hardly discussed in a world already suppressing the significance of enslaved people overthrowing their enslavers.

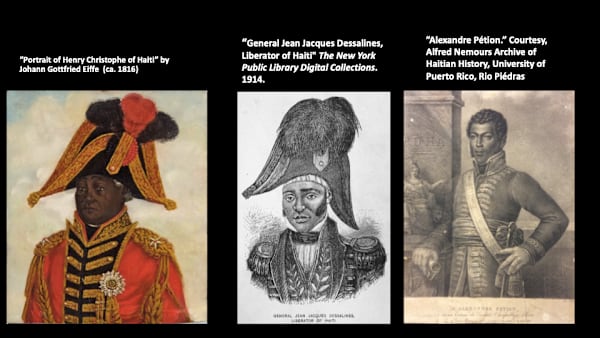

Despite such disastrous internecine struggles, under the leadership of General Jean-Jacques Dessalines, on November 18, 1803, the indigenous Haitian army defeated French troops at the Battle of Vertières and declared Haiti independent. Given command over the entire military by Dessalines, who became emperor, Christophe later found himself accused by Pétion of contributing to the plot by which Dessalines was killed on October 17, 1806. Christophe, in turn, charged Pétion with orchestrating the assassination. These conflicts led to the 13-year civil war in Haiti that would be extinguished only after both Christophe and Pétion were dead.

After Dessalines’s assassination, Haiti was split into two, with Pétion ruling in the south as president and Christophe ruling in the north under the initial title of president and generalissimo. Then, on March 26, 1811, Christophe issued a proclamation announcing that his councilors of state had just invited him to change his title to king and establish the Kingdom of Haiti. Just one week later, another edict announced the creation of the nobility, with Christophe’s most cherished friends and administrators among the dozens of dukes, counts, barons, and chevaliers named to the royal order of Saint Henry.

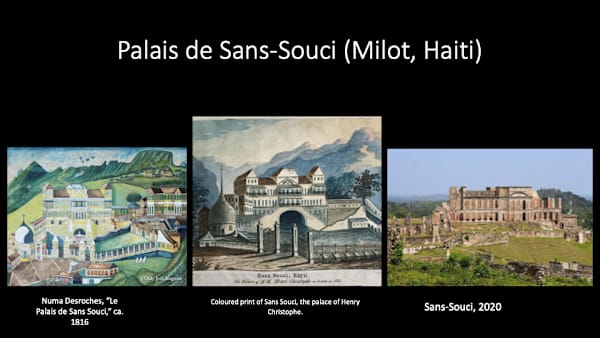

By 1813, the Kingdom of Haiti under Christophe had an even larger system of nobility, which now included the Baron de Vastey, and Christophe lived in a beautiful palace, richly adorned with complex architectural details that rivaled the most opulent structures in old Europe. Yet the construction of this palace, called Sans-Souci—some say in lugubrious recognition of the man Christophe had killed, others say after Frederick the Great’s summer chateau in Germany—led to the charges that, although he proudly proclaimed himself to be the “first monarch crowned in the New World,” the Haitian king had merely brought to it old-world despotism.

Stay tuned on Oct. 8, for another post that continues the story, as a part of my series, “On this day in Haitian History.”

To cite this article: Marlene L. Daut, “OTD in Haitian History (October 6, 1767): Birth of Henry Christophe, Future King of Haiti,” October 6, 2025 <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/otd-in-haitian-history-october-6-1767-birth-of-henry-christophe-future>

**Parts of this post are adapted from an article that originally appeared as “The King of Haiti’s Dream” at Aeon magazine: https://aeon.co/essays/the-king-of-haiti-and-the-dilemmas-of-freedom-in-a-colonised-world