By the end of the second decade of the 19th century, it had become commonplace to describe Haiti as a country split in two, one part ruled by Henry Christophe in the north and the other by Alexandre Pétion in the south. In reality, the political divisions were far more complicated and would have everything to do with King Henry's eventual downfall.

On the northern half of Haiti’s southwestern peninsula lies a mountainous region called Grand’Anse. Until February 1820, when Pétion’s successor President Jean-Pierre Boyer conquered it, Grand’Anse was controlled by a formerly enslaved man named Jean-Baptiste Duperrier, known as Goman. Partial to General André Rigaud during the Haitian Revolution— the rival of the late General Toussaint Louverture—Goman pronounced Grand’Anse independent from the other Haitian states at the beginning of the great schism. Even when Rigaud declared himself the leader of a fourth political entity on the southern side of the peninsula in 1810, Goman refused to surrender either his authority or the approximately 700 square miles over which he claimed sovereign power.

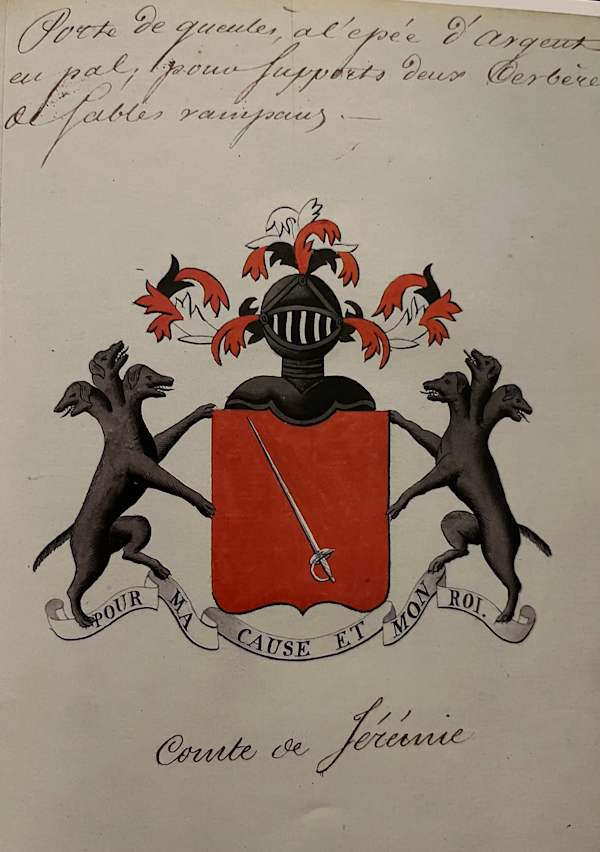

Despite refusing official incorporation into any of Haiti’s separate states—Rigaud died in 1811 and the section he ruled was shortly thereafter absorbed into the Republic of Haiti—Goman did become the Comte de Jérémie under Christophe, then a king, afterwards acepting an opulent throne and a gold cross of the order of St. Henry. Goman’s seeming deference to the king of Haiti led to natural conflict with the neighboring Republic. Pétion had previously tried and failed to overthrow Goman, and after Pétion unexpectedly died in March 1818, Boyer decided to try again.

In 1819, the Republican Army began an ardent campaign to find and capture Goman, referred to as the God of the forests, who was hiding in the treacherous Mamelles mountains. The siege only ended when Goman, surrounded on all sides by Boyer’s troops, leapt to his death from the heights of a mountaintop into the gulf below.

(Official coat of arms of Jean-Baptiste Duperrier, Comte de Jérémie, more commonly known as Goman)

When Boyer greeted the victorious soldiers in coastal Jérémie on February 18, 1820, he intimated that this was but the first victory in his plan to reunite all of Haiti: “There remains more yet for you to do!” he said. “Forever listen for my voice and be ready, at the first signal, to march with me to consolidate stability and national glory.”

To hear the king’s contemporaries tell it, Providence would soon provide an opening. On August 15, 1820, the same day that a fire raged across the capital of the Republic in Port-au-Prince, King Henry collapsed after suffering a major stroke in Limonade. The royal family and other dignitaries were attending mass there to celebrate the queen’s royal birthday and the Catholic Feast of the Assumption. After his collapse, the king’s doctor, the Scotsman Duncan Stewart, was able to revive Christophe, but the king remained partially paralyzed on one side.

When the king returned to Sans-Souci in early September, Dr. Stewart observed that though his paralysis had subsided, he had become increasingly paranoid and mistrustful. Christophe, who also envisioned reunification after Pétion’s death, claimed to have learned through spies that Boyer was plotting to attack the city of Saint-Marc—the largest city on the western boundary between the kingdom and the republic.

On September 14th, the still-recovering king received two high-ranking officers from the 8th demi-brigade of Saint-Marc, General Jean-Claude and Colonel Paulin, each of whom accused the other of colluding with the republic. Fond of the saying, “where there’s smoke there’s fire,” Christophe was known for punishing people on mere suspicion. Without hearing Paulin’s full testimony, Christophe sided with Jean-Claude and sent Paulin to prison. The regiment in Saint-Marc was partial to Paulin, however, and retaliated by murdering Jean-Claude. The border troops then delivered Jean-Claude’s head to President Boyer as they voluntarily surrendered and offered to join the Republican Army.

When Christophe learned of the October 1st defection of the entire 8th demi-brigade, he dispatched troops from the neighboring bourg of Montrouis to oppose them. But instead of defending the kingdom, they joined the Republican army, reportedly cheering in the streets, "Vive la République! Vive le Président!" By October 6th, the insurrection had spread north all the way to Cap-Henry, where the Royal Prince’s British teacher heard villagers shouting, "Down with the Tyrant!"

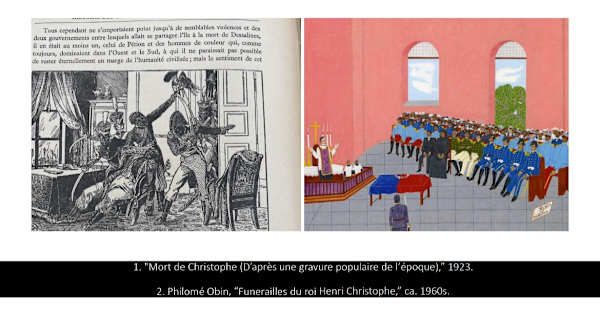

On the morning of October 8th, Christophe sent one last military brigade to try to crush the rebellion, but when he learned that those troops had also defected and joined the Republican Army, he told Dr. Stewart with resignation, “For my part, I know what I must do.” The fatal shot by which Christophe removed himself from power, and this world, rang out from his bedroom between 7:30 and 10:30 that night.

To cite this article: Marlene L. Daut, "OTD in Haitian History (October 8, 1820): Death of Haiti's First and Last King, Henry Christophe," King of Haiti's World Blog, October 8, 2025 <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/otd-in-haitian-history-october-8-1820-death-of-haiti-s-first-and-last>

*P.S. Check back tomorrow, October 9, when my "On this Day in Haitian History" series continues with something both magnificent and surprising from Christophe's early life.