By MARLENE L. DAUT

“I come back to the deadly seriousness of intellectual work. It is a deadly serious matter.”—STUART HALL, “Cultural Studies and its Theoretical Legacies” (1992)

This January has certainly been an eventful one, both politically, and perhaps, in a cosmic attempt to match the ongoing governmental mayhem we are facing, meteorologically as well. We recently had a major winter storm here in Connecticut that dumped about 18 inches of snow, sleet, and ice on the city where I live, wreaking all kinds of havoc. Even though I lived in Indiana for six years, and I have dealt with way worse winters than this, my California heart still skipped a few beats when I saw the forecast.

Yet, even though it is no secret that I truly do not enjoy snow, I have always found there to be something inherently poetic and beautiful about the kind of harsh winter we are experiencing this year. With its brutal winds bringing us to subzero temperatures, terrifying and sometimes damaging ice and snow showers, and dangerously depressing skies, winter somehow always manages to remind—no, force—me to reckon with how small I am on this planet: just one tiny organism in time, ever at the mercy of this vast universe.

Experiencing such awe at what the bigness of the world can do has encouraged me to do something very small that has been a goal of mine for quite some time. I have been talking about starting a literary salon for years. I want to read and think with engaged citizens who are interested in tackling the serious problems of our world: racism, colonialism, war, fascism, dictatorship, poverty, climate change, and inequality of all kinds. Regardless of political leaning, these are issues we all face as human beings living on this earth. And we all have a responsibility to try to eradicate injustice.

I have been reading a lot on my own, to that end, and trying to share the knowledge I have gleaned with those in my personal circles, but I want really want is to be in dialogue with as many people as possible, especially with those also interested in how we can most impact and change this world for the better.

In my quest to read more and learn more about topics less familiar or even totally unknown to me, I am therefore reading a lot of books that have nothing to do with Haiti and/or the Caribbean. If you’d like to join me in a little virtual reading salon that I am calling The Write House Literary Circle, please pick up Timothy Snyder’s On Freedom. Despite the simple enough title, the book promises a sweeping examination of how freedom has been conceptualized, intellectualized, distorted, and even weaponized for centuries, including in Nazi Germany and Stalinist Russia, and, of course, throughout the long history of the United States of America. I am only at chapter two so far, but the way things are going this book is sure to be one of my favorite reads this year. I only hope that at the end Snyder may offer us a path, not just for survival but for renewal.

Unlike winter, which will inevitably give way to spring and then to glorious summer (my favorite time of year), the current political path we are on as a nation is clearly not going to change, along with the seasons, unless we, as a collectivity, make it; our situation is so unsustainable at the moment that it can only inevitably end in destruction, perhaps, of our nation alone, perhaps, of the entire world.

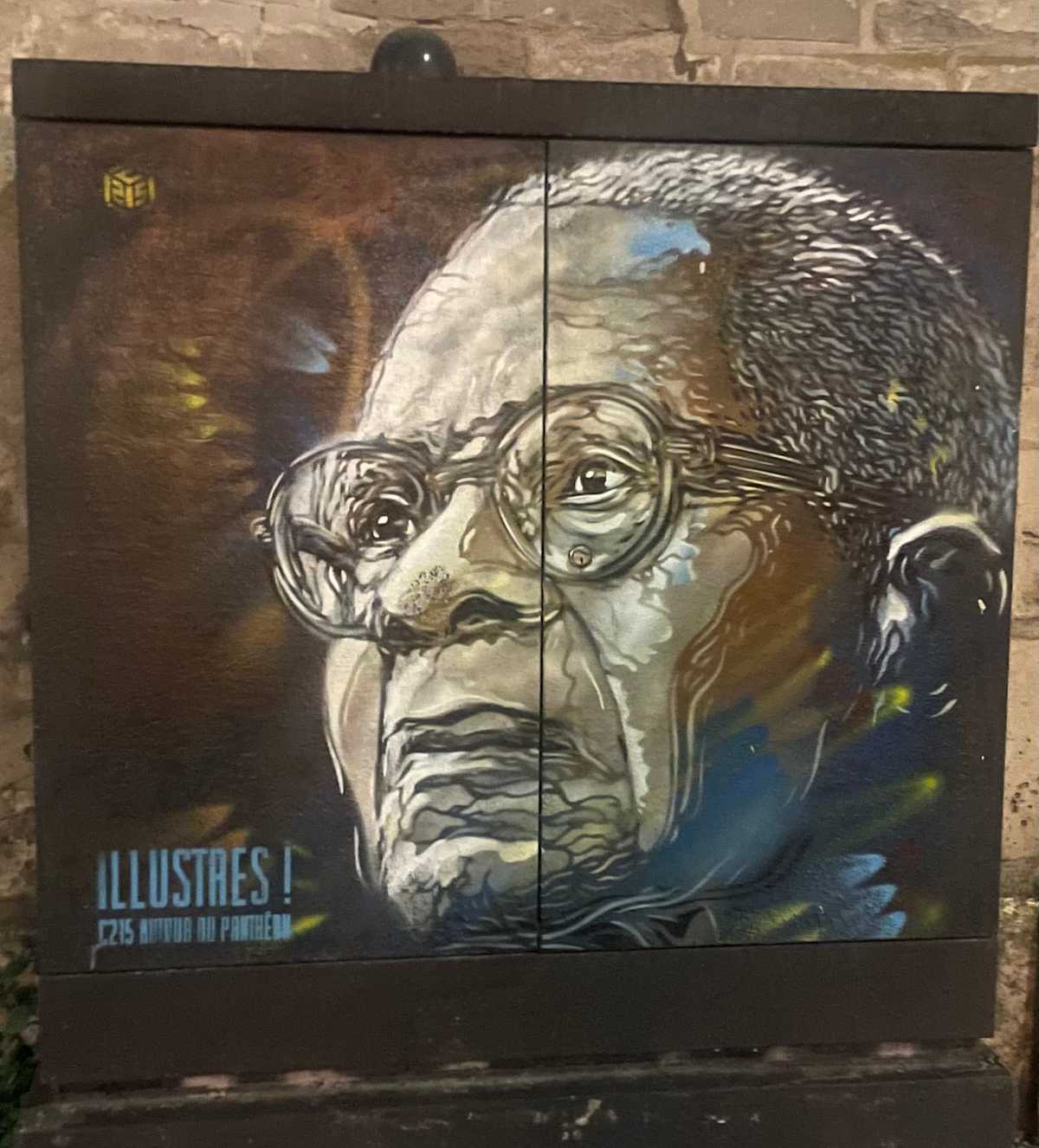

Teaching gives me one outlet for thinking and reflecting on what there is to be done. This semester, I am teaching an entire graduate seminar devoted to understanding the life and works of Aimé Césaire, and in a few weeks we will be discussing a text that I teach almost every semester, Discourse on Colonialism. This essay is truly so rich and instructive—I honestly glean something new from it on every additional read—with its many now famous maxims and aphorisms about the destructive intersections of colonialism and capitalism, among which:

“No one colonizes innocently…no one colonizes with impunity either…a nation which colonizes…a civilization which justifies colonization—and therefore force—is already a sick civilization.”

“Colonization: bridgehead in a campaign to civilize barbarism, from which there may emerge at any moment the negation of civilization, pure and simple.”

“My turn to state an equation: colonization= ‘thingification’. I am talking about societies drained of their essence, cultures trampled underfoot, institutions undermined, lands confiscated, religions smashed, magnificent artistic creations destroyed, extraordinary possibilities wiped out.”

“Do you not see the prodigious mechanization, the mechanization of man, the gigantic rape of everything intimate, undamaged, undefiled that, despoiled as we are, our human spirit has still managed to preserve; the machine, yes, have you never seen it, the machine for crushing, grinding, degrading peoples?”

In my other course, Haiti Writes II (co-taught with Professor Kaiama Glover), we are examining the corrosive politics of the past (and present) in more abstract and poetic (but no less forceful) terms. Turning to the Haitian novelist and poet René Depestre this past week, we could not but help to marvel at how he tried to warn us in his A Rainbow for the Christian West (tr. Colin Dayan):

My green gods recoil in terror

Before them stand aligned

The great gods of the nuclear age

The creators of homicidal suns

…

Murderers of space and time

I translate for my gods

The secret messages

These missiles send to earth

“Down with human beings”

…

Tomorrow the H Bomb!

The gods of my native village

Are suddenly child-gods

Who curl up against me

They see the revolution of ashes coming

The earth disrobed by H Bombs

The outline of millions of bodies on the walls

The starving tigers from one hundred thousand suns

Throw themselves down on the world in a single stroke

And the fathers of my roots tremble

…

Green angels of the earth and sky

Here they are at my side, robbed of power,

Disarmed and conquered by these new gods

Gods of heavy water and cobalt

Who have never had a childhood, who have never

Built sand castles

And have never wept all night without reason

While listening to the rain fall in their inner being

Oh, carrier of murderous stars

Do not laugh at my agrarian gods

Because they have not broken the bridges

With the first salt of the earth: Man!

If we want the world to be good, then we have to make it so. Part of that involves education and another part involves not simply tolerance and dialogue but what the Martinican philosopher, playwright, and novelist Edouard Glissant called relation. In its most basic formulation, Glissant has described “relation” as the acceptance of difference. “Everyone likes broccoli but I hate it,” Glissant once said:

“But do I know why? Not at all. I accept my opacity on that level. Why wouldn’t I accept it on other levels? Why wouldn’t I accept the other’s opacity? Why must I absolutely understand the other to live next to him and work with him? That’s one of the laws of Relation. In Relation, elements don’t blend just like that, don’t lose themselves just like that. Each element can keep its, I won’t just say its autonomy but also its essential quality, even as it accustoms itself to the essential qualities and differences of others.”

While we may not all be able to hit the streets like the brave protesters in Minnesota, living as we do in societies called nations, we are all responsible for what happens to each other. We cannot close our eyes and pretend that nothing is wrong. As Césaire wrote in his famous Notebook of a Return to my Native Land, "...beware of assuming the sterile attitude of a spectator, for life is not a spectacle, a sea of miseries is not a proscenium, a man screaming is not a dancing bear…”

I will leave you, then, with the searing (and indicting) words of the poet Canisia Lubrin from her recent book, Code Noir:

“The murderers in this draft are those who write the laws….If you are here, you know by now that the bankers are useless though dangerous; the kings are flies; the craven philosophers with some of their poet friends, have left for the mountains; and the rest of us, we are somewhat bored with it—all of it—and somewhat overcome. So, keep pace with what is about to happen in these pages. If anybody gets to preaching, you point them to the footnotes. If anybody tells you they have the only truth, you use your nose instead. If anybody claims innocence, stop them. If anybody tells you everything is working fine, run.”

Let us all read more, learn more, and act more to create the humane world we want.

How to cite this essay: Marlene L. Daut, "The Deadly Seriousness of Reading and Learning," King of Haiti's World Blog, January 30, 2026. <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/the-deadly-seriousness-of-reading-and-learning-by-nbsp-marlene-l-daut-i>