By Marlene L. Daut

Back in 2021, I wrote an article called “Why did Bridgerton erase Haiti?”. In the article I asked a deceptively simple question:

“If people want to see Black aristocracy on screen, then why not just put them in nineteenth-century Haiti where they really lived?”

Simon Sebag Montefiore, who reviewed my book, The First and Last King of Haiti, for The Times of London evidently wondered the same thing when he wrote:

“I don’t know if the makers of Bridgerton, Netflix’s glossy late Georgian alternative-history-romance, have read about King Henry, but his story could inspire a more accurate, important and sober but no less glamorous spinoff, especially because Queen Marie-Louise later lived in London.”

Montefiore is not the only the person I have encountered to have observed that the life of Haiti’s only king, and the awe-inspiring kingdom he built, would make a great movie, limited series, or even a musical.

After I told him about how as a 12-year old child the future King Henry fought in the American revolutionary war at the Battle of Savannah and then went on to participate in the Haitian Revolution and from there to create the Kingdom of Haiti, Colin McEnroe of CT Public Radio said, “wait a minute, I smell a Lin-Manuel Miranda musical;” while Jordan Lauf of WNYC’s show “All of It,” couldn’t help but to agree, when, after recommending The First and Last King of Haiti to listeners as a spring read (!), she said, “The story is just an epic tale. Honestly, maybe Lin-Manuel Miranda wants another inspiration for a musical, as this guy's life is pretty nuts;" and although San Francisco may be about 400 miles from Los Angeles, I sure hope someone from Hollywood was listening back in January when I had the chance to talk to host André Senior at Fox Channel 2 out of San Francisco about The First and Last King of Haiti. The conversation took an interesting (and thrilling!) turn at the end when Senior remarked, “I can’t wait for the movie!”

But I must say, the moment when I knew that the universe was really trying to tell me something was when the former book review editor for The Hollywood Reporter, Andy Lewis, reviewed The First and Last King of Haiti on his Substack, The Optionist. The newsletter is designed to in his words, “do some of the reading for [producers and filmmakers],” looking for their “next great projects to develop during these streaming wars.” Here’s what he said about the potential for The First and Last King of Haiti:

"Daut’s account of Christophe's life could easily make a fantastic biopic. He comes across as a complicated figure and not the stereotypical dictator as he's often portrayed. Christophe was a reformer and an autocrat, a freedom fighter and betrayer of his country. It's a grand, epic life that seems tailor-made for the screen. Daut's deeply researched and nuanced portrayal is exactly the kind of underlying IP that a good screenwriter needs to craft a compelling script.

It’s also a dream part for an actor. What Black star (Michael B. Jordan, Mahershala Ali, Daniel Kaluuya) wouldn't want a shot at an instant awards-bait role like this one? Getting the right name to sign on might just be the thing to get it off the ground."

I couldn’t agree more with Lewis that with the right actor advocating to play King Henry or his wife, Queen Marie Louise, or any other character in this epic tale, The First and Last King of Haiti, the movie or the series, could really happen, especially, if the past is any indicator of the present.

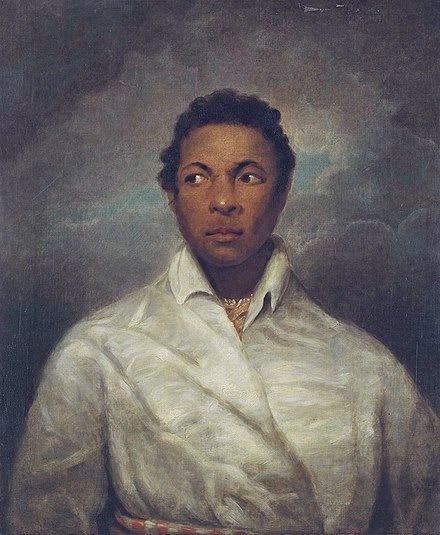

As I wrote in the biography, and also, right here on this very blog, since the 19th century, Black actors have craved the chance to play King Henry Christophe. The famous American-born Black actor Ira Aldridge was the first to seize the opportunity when he played the Haitian King in J.H. Amherst’s “Death of Christophe, King of Hayti” in the 1820s at London’s Coburg Theatre. Aldridge was followed by a string of stars from all over the world: Jack Carter, Rex Ingram, William Dubois, Errol John, and Douta Seck, to name just a few. Yet perhaps the most famous Black actor who longed to play Christophe was Paul Robeson.

Robeson, who starred in Eugene O’Neill’s famous Emperor Jones in 1933, once told a reporter: “The most interesting thing I can see ahead for next season is the musical play that Jerome Kern and Oscar Hammerstein may do, based on Black Majesty, the story of Emperor Henri [sic] Christophe, who built his great citadel in Haiti and defeated Napoleon’s troops. It sounds like great material, doesn’t it?” Although it never panned out, another huge production by none other than Orson Welles did, and to great success.

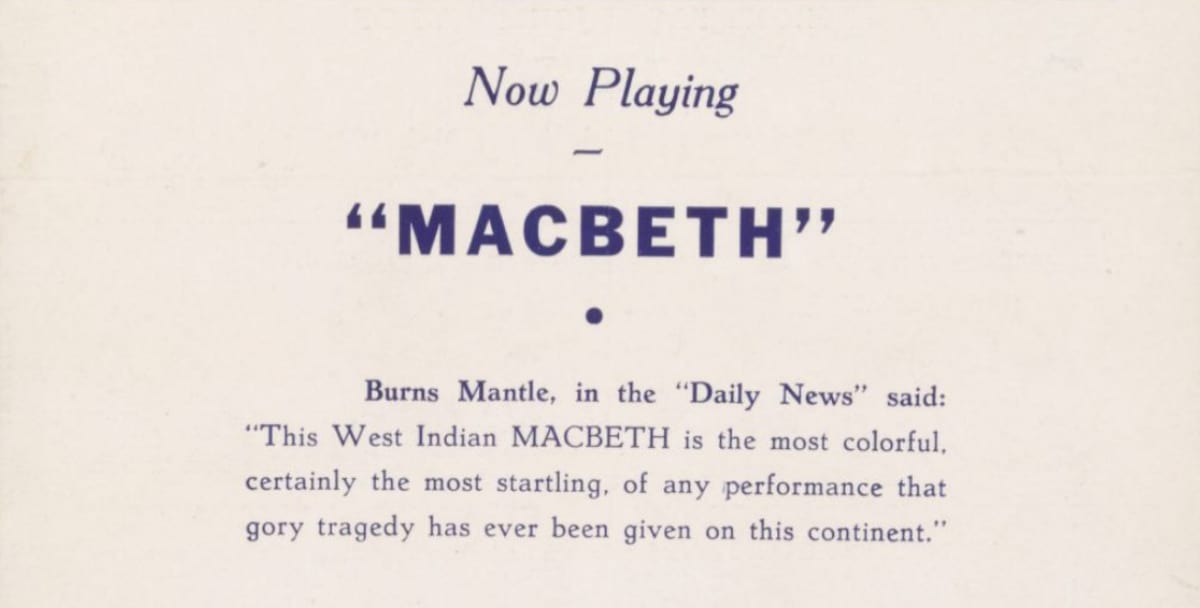

Yet it wasn’t to John Vandercook’s 1928 novel about King Henry, Black Majesty, that Orson Welles looked in trying to find a way to bring Christophe’s story to the stage, but instead to William Shakespeare’s Macbeth. On April 14, 1936, twenty-year old Orson Welles directed his first major play, an adaptation of Macbeth with an all-Black cast. Debuting in Harlem’s storied Lafayette Theatre, the play sold out every one of its 1,223 seats. Ten blocks on either side of the theatre had to be shut down due to the overwhelming crowds, and a police escort was required to lead the ticketed through the throng. Though Welles is perhaps most remembered for directing and starring in the 1941 film, Citizen Kane, which earned nine Academy Award nominations, it was his sensational—and Black—Macbeth that first made him a star.

Newspapers critics from across the United States generally extolled the adaptation, with Welles admitting that the story and setting was loosely based on the life of King Henry Christophe and his early nineteenth-century kingdom. Critics expressed fascination for Welles’s substitution of Haitian Vodou for the play’s original and more nebulous witchcraft. But this unheard-of transposition, with the attendant stereotypes about Haiti and Haitians that it brought to life, eventually earned the popular stage production the problematic nickname “Voodoo” Macbeth.

Scripts plagued by racism, either implicit or overt, as well as general anti-Haitianism (I’m looking at you, Black Majesty!), have historically been part of the problem with bringing not just the Haitian Revolution to the big screen, but with staging the intriguing, vexing, and utterly compelling story of King Henry Christophe.

In fact, the Hollywood actor James Earl Jones, who passed away in 2024, previously confessed that in the 1970s, when offered the opportunity to play Haiti's Henry Christophe on screen, he and other Black actors had refused because, in his words, “we have not yet received a script that does the man's life justice." The fact that fiction-writers, in particular, have not been able to fully tell Christophe’s story without prejudice and bias was one of my primary motivations for writing a biography.

I believe in the transformative power of books, so writing a biography was my chosen outlet. Yet I also think that visual media offers an unparalleled opportunity to re-shape the narrative around Christophe, and in so doing, to teach the world a little something about Haiti and its fascinating history. This is what has led me to my current project.

Drum roll , please!

Instead of waiting and hoping that some big Hollywood type notices my book and wants to either option it or outright adapt it for the screen, I have decided to be more proactive and write the screenplay myself.

The late Toni Morrison famously said in a 1981 speech for the Ohio Arts Council: “If there's a book that you want to read, but it hasn't been written yet, then you must write it.” In much the same vein, if there is a film or a television series that we, as Haitians and/or people of Haitian descent, want to see in the world, then we have to write it. And that is precisely what I am trying to do.

Since Hollywood has not yet come calling—despite all the obvious appeal of the story!—I have been taking screenwriting classes from two very experienced and extremely encouraging instructors, and hopefully soon, I'll even have a full draft of a screenplay to show for it. I know that people all around the world are interested in and intrigued by Christophe's life: the book has a separate UK edition, an excerpt of my book ran in the Mail & Guardian, out of South Africa, and a short 5-minute video that I created about the King of Haiti for Ted-Ed way back in 2020 has amassed more than 600,000 views and has been translated into 24 languages, including Haitian Creole, French, Spanish, German, Indonesian, Japanese, Korean, Kurdish, Polish, Arabic, Italian, Dutch, and Mandarin. So, the problem is clearly not lack of interest or lack of audience. Perhaps, the problem is simply that writers and directors are not sure how to tell this amazing but complex story on screen.

In writing the screenplay myself, then, I am merely trying to smooth what might seem like a daunting path. As Andy Lewis observes on his Substack (and echoed by one of my screenwriting teachers), “reading and keeping up is, as you all know, exhausting.” Indeed, it's a lot to expect someone to read a 650+ page book and then pull out all the relevant stories, or to be able to perceive all the angles that are most ripe for adaptation without fully knowing the history.

Now seems like a good time to stress, however, that this new screenwriting project is not meant to be a documentary. Instead, it is going to be a work of historical fiction, or as they say in Hollywood “inspired by the life of….”

Ultimately, my hope-dream (to use the language of my other screenwriting teacher) is that a producer, screenwriter, or director, after reading my script (si bondye vle), will be able to see the shape that this story might take on screen. In fact, I have already produced a show "bible" describing all the characters, the world, the tone, and the overall arc of the story. I want filmmakers not to be intimidated but inspired by the magnificence of Christophe's life, which had more twists, turns, and surprises than anything a novelist or playwright could dream up.

Screenwriting and/or trying to get your book optioned is enormously complicated. It involves so much careful dancing with budgets and writers, scripts and studios. I mean, maybe some people just get lucky and have producers contact them and therefore never have to think about any of this, but my given my trajectory in this world, I have never been one for just waiting for the luck to happen. Like my ancestors, I know that we must make our own.

To cite this article: Marlene L. Daut, "Adventures in a New Genre: On Screenwriting!", August 9, 2025, King of Haiti's World Blog <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/adventures-in-a-new-genre-screenwriting-by-marlene-l-daut-nbsp-back-in>