By Marlene L. Daut

In my first blog post of 2026, I want to mark the fact that today is the one-year anniversary of the publication of The First and Last King of Haiti. I remember last year at this very time, I was busy trying to finish up my syllabi for the impending semester (check, for this year too!), as I anxiously awaited the possible publication of early reviews and/or for a few podcast episodes I had pre-recorded to drop. In truth, I spent most of the day in a state of ambivalent anticipation/apprehension. I did not really know what to do with myself, which is actually quite a common experience on book publication day.

As authors, we spend so much time in anticipation of our book pub day that when the day itself arrives it can feel all at once, or by turns, anti-climactic, anxiety-inducing, and even disappointing. I am sure I felt all these things as the minutes and then hours ticked by. For all those publishing on this day in 2026, or one day soon this year, I raise my fist in solidarity to you, and say that, this day, too, shall pass, and then you, like me, will likely look wistfully upon it in a year or so.

I’ve certainly found ways to keep myself busy today, I must say, though. In fact, I’ve already had quite an exhilarating day (having made the early mistake of listening to the news, notwithstanding!). This morning, I took a little trip over to Danbury, CT, riding alongside the scenic Housatonic River, to reach the Western Connecticut State University 2026 Winter Residency Program. Why did I do that? I was invited by the director, Anthony D’Aries, to lead a session, which I ended up calling “Writing at the Margins of Fiction and History: The Case of the Haitian Revolution.” I had a great time chatting with the students (who definitely made me feel nostalgic for my days as undergraduate major in creative writing), other instructors, and even a dean from the university who showed up.

One of the things I discussed in my session was my turn to more public-facing writing around 2018-2019, after I participated in the Op-Ed Project, and which also coincided with my appointment as an editor at Public Books in the Global Black History section. I truly love being an editor, which affords me the opportunity to read, talk about, and review other people’s books. And last year, around this very time, I promised myself that once my own book publication madness subsided, I would not only continue to robustly commission book reviews, but I would write more book reviews myself. And I am happy to say that in 2025, I reviewed, recommended, or end-of-year-listed quite a few books (here too).

I plan to continue trying to commission and write as many book reviews as I can in 2026, but another promise I am making to myself for 2026 is to talk more about the museum and art exhibits I visit. I am a fairly avid participant in museum and art culture, and yet I rarely write about them. But if the book review landscape, in terms of available opportunities and outlets for publication, is undoubtedly bleak, the number of places to land an art review (especially if you are not an art critic by trade) is practically non-existent, and only disappearing more and more by the year. This means that many an amazing museum exhibit or art show passes through the world with hardly a whimper in the media.

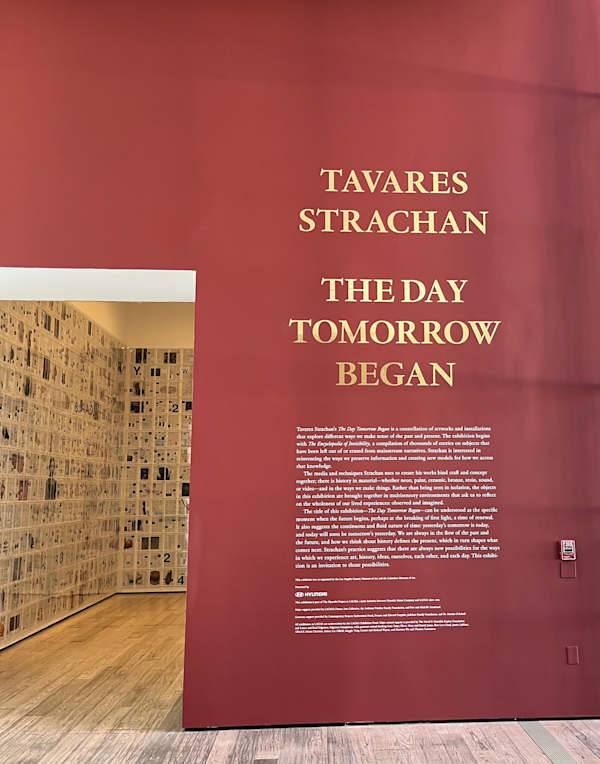

So, I thought I would finish this first blog post of the year by briefly noting that this December, over the winter break, while visiting family in southern California, I had the remarkable opportunity to visit Tavares Strachan’s latest show, The Day Tomorrow Began, on exhibit at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art (LACMA). What drew my interest in the exhibit was an article published about the show in Alta. The magazine included a photograph of the largest sculpture in Strachan’s show, In Praise of Midnight (Christophe x Napoleon). True to its title, the sculpture, which is a part of what Strachan terms “Monument Hall,” features General Henry Christophe, donning his military uniform, mounted atop an upside-down rendition of his arch-nemesis, General Napoléon Bonaparte, who also appears in military garb.

(Tavares Strachan, In Praise of Midnight (Christophe x Napoleon), LACMA, photograph by Marlene L. Daut, copyright 2025)

(Tavares Strachan, Monument Hall, LACMA, photograph by Marlene L. Daut, copyright 2025)

The portrayal of these enemy leaders sculpted into infinite duel hit me like a gut punch. Although, the hierarchical positioning of the two figures suggests that Strachan is quite well-versed in Christophe’s heroic role in the Haitian Revolution and Bonaparte’s genocidal one, I also know that Strachan could have just easily chosen to feature Jean-Jacques Dessalines toppling Bonaparte, or more immediately, he could have opted to give us the much more famous and well-known Toussaint Louverture. But when thinking about people and events that are often (and quite deliberately) left out of encyclopedias, which is one of the major focuses of the whole exhibit—the show opens in an entire room wall-papered in pages of an encyclopedia overlaid with various images, some by Strachan, some displaying historical prints by others—it is actually Christophe’s tragically personal encounter with Napoléon that stands on far less well traversed territory.

(Tavares Strachan, The Encyclopedia Room, LACMA, photograph by Marlene L. Daut, copyright 2025)

Of course, Christophe fought against Bonaparte’s troops in Haiti’s war for independence during the disastrous, and again, genocidal, Leclerc expedition. Yet Christophe’s family history also intersected (and fatally so) with Napoléon’s subsequent reign as emperor of France in ways that are little known and even less discussed.

Just before Bonaparte’s troops began their genocidal war in the name of restoring slavery, Haiti’s future king sent his son, François Ferdinand, to the Collège de la Marche, the same school that Louverture’s children had previously attended.

However, after the Haitian revolutionaries defeated France and declared the island independent in 1804, Napoléon ordered the collège closed. Many of the school’s Black students, like young Ferdinand, were then thrown into orphanages, sent to work camps, or abandoned in the streets. Ferdinand unfortunately found himself eventually among the latter. The result was that Christophe’s son died in the streets of Paris, in July 1805, after suffering a severe beating by a shopkeeper. He was only 11.

To me, the sight of Christophe toppling Bonaparte felt like glimpsing a cosmic correction of history unfolding before my eyes (even if only in my own imagination). What could have been, in another world, but never was, in our own, produced a genre of poignant identification for me that I can only describe as a feeling of triumph. (I seriously felt the urge to cheer!). Strachan's re-imagining of the possible, when placed in light of the kind of buried history represented by the silencing in world history of Napoléon’s de facto murder-by-negligence of Christophe’s child, felt like an especially urgent and necessary inversion: a reclamation and a rejection of the idea that what happened to this child, like all that has since befallen Haiti, was inevitable.

For, in truth, the buried story of this one Haitian child’s death remains only one small part of an even larger buried history: that of the world-historical significance of the Haitian Revolution against slavery and colonialism and the crushing response of the world powers who sought to stop Haiti's progress by any means.

The Strachan exhibit's greatest success may just be that with its many inversions of the past it invites us to question what we might all still make possible in the future.

How to cite this essay: Marlene L. Daut, "Whose Story Gets to Be Told? : The King of Haiti in the Work of Tavares Strachan," King of Haiti's World Blog, January 7, 2026. <https://marlenedaut.com/blog/whose-story-gets-to-be-told-the-king-of-haiti-in-the-work-of-tavares>